Sudan Security Report: al-Fashaga clashes on the border with Ethiopia

Summary

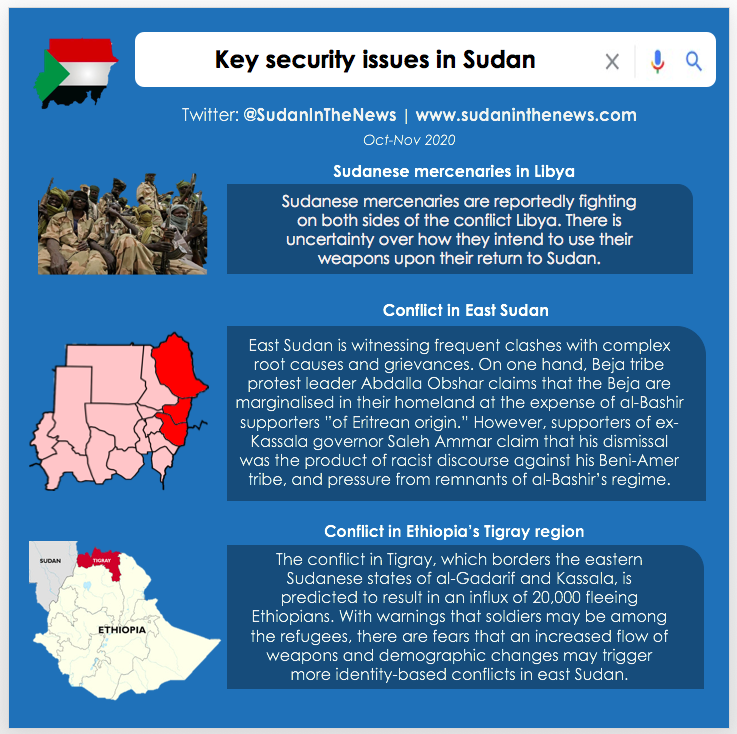

1. Events: Tensions are escalating between the governments of Sudan and Ethiopia in the border area of al-Fashaga, where Sudan’s eastern state of al-Gadarif meets Ethiopia’s north-western Amhara region. As the border has never been clearly demarcated since Sudan’s independence, tens of thousands Ethiopian farmers have been cultivating land under the protection of Ethiopian militiamen locally known as shifta, who the Lands Committee of al-Fashaga allege are “wreaking havoc” in order to expand the farmland under their control. Indeed, between May 2020 and 15 January 2021, shifta have reportedly killed at least nine Sudanese civilians and 28 soldiers, and kidnapped ten civilians. The Ethiopian government has also accused Sudanese forces of killing civilians.

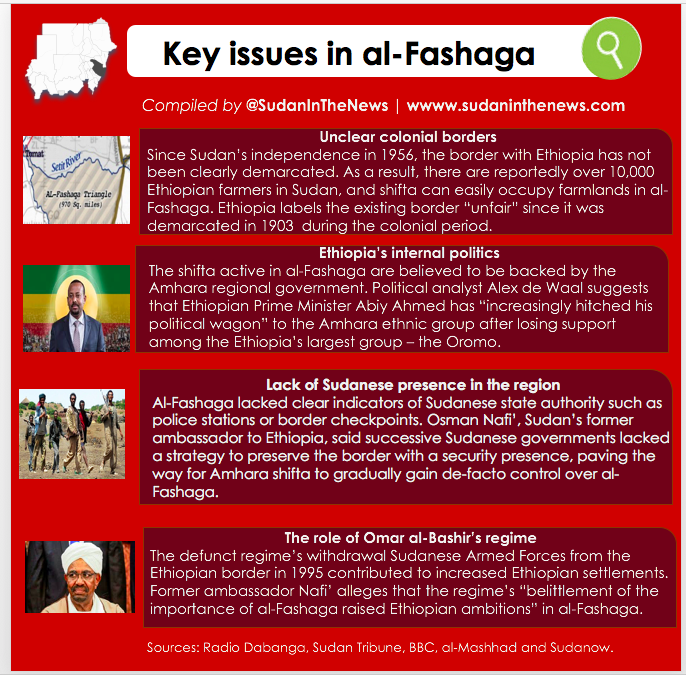

2. Issues: Among the key issues contributing to the insecurity in al-Fashaga noted by analysts and diplomats is the failure of consecutive Sudanese post-independence governments in establishing clear indicators of Sudanese state authority over the region, with Omar al-Bashir’s defunct regime particularly accused of paving the way for Amhara militant incursions. In addition, Ethiopia believes that the border demarcation with Sudan is “unfair” as it was drawn in the colonial era (1903). Furthermore, the shifta are suspected to have support from Ethiopia’s Amhara regional governorate, an increasingly important support base for Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed.

3. Solutions: Proposed solutions to resolve the issue include economic cooperation between Sudan and Ethiopia, immediate security measures to protect Sudanese civilians and legal measures to enhance Sudan’s authority over the region.

1. Events

May 2020: Ethiopian militiamen “supported by the Ethiopian army” killed a Sudanese army captain (Radio Dabanga, 12 October).

July 2020: Farmers in al-Fashaga, backed by al-Gadarif governor Suleiman Ali, demand the return on land that Ethiopian farmers have been cultivating under the protection of Ethiopian militias (Radio Dabanga, December 24).

August 2020: Shifta reportedly stole 9,000 cows, sheep and camels, committed murders and were involved in kidnapping in al-Fashaga locality (Radio Dabanga, 12 October).

October 2020

10- The Lands Committee of al-Fashaga complained that Ethiopian militiamen (locally known as shifta) were wreaking havoc on Sudan’s eastern state of al-Garadif near the border with Ethiopia, preventing farmers from harvesting sesame crops. According to the Committee, the shifta were controlling Sudanese agricultural lands and they launch sporadic attacks during the harvest season on areas not under their full control in order to steal the crops.”

15- Radio Dabanga (15 October) reported that six Sudanese women and a child were kidnapped by Ethiopian gunmen. The al-Fashaga Lands Committee said in a statement that the kidnaping occurred in the agricultural lands adjacent to al-Leya village in al-Gureisha locality, while the women were tilling their farms on the eastern bank of the Atbara River.

30- Radio Dabanga (30 October) reported that two Sudanese farmers were killed and two other men were abducted by shifta in east Galabat in al-Gadarif. A ransom was demanded for the latter. In a separate incident, another farmer was shot.

December 2020

3- The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) took control of the area of Khor Yabin in eastern al-Gadarif for the first time in 25 years. A Radio Dabanga (3 December) military source in al-Fashaga confirmed the deployment of the armed forces in half of the area that was formerly occupied by shifta.

18- 27 members of the Sudanese army were killed in an ambush by Ethiopian militiamen and armed forces as the Sudanese troops were patrolling near Jabal Abu Tuyour in al-Fashaga (Radio Dabanga, 18 December).

24- Border demarcation negotiations between Sudanese and Ethiopian government delegations in Khartoum concluded without any results. Radio Dabanga (24 December) sources say the negotiations failed because the Ethiopian delegation refused to recognise the 1903 border demarcation, saying that the British-Ethiopian treaty on the border was signed in colonial times.

27- The Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) reclaimed territory from Ethiopian army soldiers and militiamen in al-Gedarif, regaining over six Ethiopian camp sites in al-Fashaga and 11 other sites near the al-Gedarif-Ethiopian border (Multiple sources, 27 December).

January 2021

2- Chairman of Sudan's Sovereign Council, Lt Gen Abdelfattah al-Burhan, announced that the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) have been redeployed at Sudan’s border with neighbouring Ethiopia. The SAF "have not and will not cross international borders or attack neighbouring Ethiopia," al-Burhan stressed (Radio Dabanga, 2 January).

6- The Sudanese army repulsed two attacks carried out by Ethiopian forces and managed to capture one of the attackers in the Sariba border area of al-Fashaga (Sudan Tribune, 6 January).

6- Dina Mufti, spokesman for Ethiopia’s Foreign Ministry, alleged that Sudanese troops are “killing many civilians” in skirmishes in al-Fashqa. Mufti said Ethiopian authorities observed Sudanese military forces carrying out organised attacks using heavy machine guns and armoured convoys at their border. Ethiopian farmers in the region had their properties looted, while “many civilians have been murdered and wounded,” Mufti added (Bloomberg, 6 January).

12- Ethiopia warned Sudan that it is “running out of patience” with the continued military build-up in the disputed border area of al-Fashaga. “The Sudanese side seems to be pushing in so as to inflame the situation on the ground,” Ethiopian foreign ministry spokesman Dina Mufti said (Reuters, 12 January).

13- Sudan’s Foreign Ministry alleged that an Ethiopian military aircraft crossed the Sudanese-Ethiopian border in a ”dangerous and unjustified escalation”. The incident “could have dangerous consequences, and cause more tension in the border area”, added Sudan’s Foreign Ministry, which called on Ethiopia not to repeat “such hostilities in the future given their dangerous repercussions on the future of bilateral relations between the two countries and on security and stability in the Horn of Africa” (Reuters, 13 January).

13- Seven Sudanese civilians were killed (six women and a one-year-old child) when shifta attacked the village of Leya in al-Gureisha localiy in al-Gadarif. The attack was launched when the victims were harvesting corn. A local civilian named Mousa Saleh was also kidnapped and held for ransom (Radio Dabanga, 13 December).

14- Sudanese political leaders called for the expulsion of the Ethiopian ambassador following his “provocative statements,” after he accused the Sudanese army of seizing “nine areas belonging to Ethiopia”. He claimed that British border demarcation officers sided with Sudan and drew unfair borders in colonial times, meaning that Ethiopian citizens cannot be removed from the area (Radio Dabanga, 14 December).

14- The head of Sudan’s National Border Commission, Dr Moaz Tango accused Ethiopia of neglecting its responsibilities and obligations regarding border agreements since they were defined in 1903. According to Tango, the Ethiopian government acknowledged the validity of Sudan's position regarding control of the disputed lands, saying that his Ethiopian counterpart did not call for a review of the agreement in their previous meetings (Sudan News Agency, 14 December).

15- Sudan’s Civil Aviation Authority (SCAA) declared the closure of airspace over al-Fashaga. Aeroplanes will not be allowed to fly above al-Fashaga under an altitude of 29,000 feet. The restriction is effective from January 14 to April 11 (Multiple sources, 15 January).

15- Information Minister and government spokesperson Faisal Mohammed Salih said Sudan is not looking for a war against Ethiopia, but it will not hesitate to defend its citizens and territory (Sudan Tribune, 15 January).

15- Sudan Tribune (15 January) also reported that foreign minister Omar Gamraldin rejected calls for mediation from the Ethiopian government. "Sudan does not seek any mediation with Ethiopia, because it is our borders and our land, (...) We also do not admit that we are in a border dispute to resort to arbitration, " he stressed. "When Ethiopia calls the border ’disputed’, this is a false description that finds no legal basis in the international law,’ he added.

16- Sudan Tribune (16 January) reported that al-Burhan said he agreed with Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed to deploy Sudanese troops to “prevent border infiltration to and from Sudan by an armed party,” and that he said the army has no intention to wage war against Ethiopia, or cross into the border.

2. Issues

Colonial borders

Since Sudan’s independence in 1956, the 1,600 kilometre border with Ethiopia has not had a clear demarcation, thereby making it easy for Ethiopian militants to occupy farmlands in eastern al-Gadarif’s al-Fashaga (Radio Dabanga, 24 December). According to the head of Sudan’s National Border Commission, Dr Moaz Tango, Ethiopian “encroachments” on Sudanese lands began in 1957 with three Ethiopian farmers, eventually continuing to a level where there are over 10,000 Ethiopian farmers cultivating Sudanese farmland (Sudan News Agency, 14 January). However, Ethiopia’s claim to al-Fashaga is on the basis that it does not recognise the 1903 Ethiopia-Sudan border demarcation as it was signed during the colonial period (Radio Dabanga, 24 December). Indeed, Ethiopia’s ambassador to Sudan labelled the borders “unfair”, meaning that Ethiopian citizens cannot be removed from the area (Radio Dabanga, 14 January).

Internal politics of Ethiopia

Ethiopia’s internal politics point to the possibility that ethnic Amhara militiamen have state support. Such suspicions are present among the highest levels of Sudanese government, as indicated by government spokesperson Faisal Mohammed Salih referencing the training and armament of Ethiopian forces that attack the Sudanese army, stressing they are not "armed militias or farmers", in what Sudan Tribune (15 January) wrote was “an allusion to the Fano paramilitary force who are [sponsored] by the Amhara region”.

Explaining the roots of the dispute between over al-Fashaga region “where the north-west of Ethiopia's Amhara region meets Sudan's al-Gadarif,” Africa analyst Alex de Waal highlights a 2008 agreement in which Ethiopia acknowledged that the land belongs to Sudan, but Sudan permitted Ethiopians to continue living there and paying taxes to Ethiopian authorities. However, ethnic Amhara leaders in Ethiopia objected to the deal.

The Ethiopians who inhabit al-Fashaga are ethnic Amhara – Ethiopia’s second largest group and “its historic rulers,” – a constituency that Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has “increasingly hitched his political wagon to after losing significant support in his Oromo ethnic group (Ethiopia’s largest)” (BBC, 3 January).

Indeed, local farmer Alrasheed Abdelgadir alleges that official Ethiopian forces sent by the Ethiopian Federal Government are operating “a carefully designed plan to build settlements, towns and infrastructure that provide food and services free of charge to attract more people to the area” (Sudanow, 17 January).

Lack of Sudanese presence in the region

Al-Tahir Satti, the editor-in-chief of al-Saiha (19 December) newspaper, attributes the fragile security situation in al-Fashaga to the lack of government presence in the region, despite al-Fashaga being “Sudanese land according to international maps, and in the absence of Ethiopia regimes claiming otherwise.”

Veteran Sudanese legal academic Dr. Faisal Abdulrahman Ali Taha, who authored a book published in 1983 entitled ‘The Sudan-Ethiopia Boundary Dispute’ questioned why al-Fashaga lacks Sudanese police stations, border checkpoints or a clear indicator of Sudanese state authority. Dr. Taha further suggested that “Ethiopian encroachment on Sudanese territory must have been entrenched within decades,” thereby “raising suspicions of collusion, negligence, and possibly corruption at the local or national levels” (Al-Rakoba, 14 January).

Indeed, Osman Nafi’, the former Sudanese ambassador to Ethiopia attributed Ethiopian expansion to state governors acting out of personal rather than national loyalties in their dealings with Ethiopians, adding that successive Sudanese governments lacked a strategy to maintain the border with Ethiopia through a security or population presence (al-Mashhad, 15 January).

The role of Omar al-Bashir’s defunct regime

As noted by Sudan Tribune (16 January), al-Bashir is accused of “facilitating the occupation of Sudanese borderland for over 20 years”. Current Sudanese head of state Lt. Gen. Al-Burhan said that when he was previously station on the border, the regime gave instructions to withdraw, in a reference to the Sudanese Armed Forces exit from al-Fashaga in 1995, which Sudanow (17 January) wrote: “[resulted in] Sudanese farmers being left at the mercy of Ethiopian gangs.” Former ambassador Osman Nafi’ attributed “raised Ethiopian ambitions” on the border to al-Bashir’s regime “belittling the importance of al-Fashaga” and its pre-occupation with internal wars.

3. Solutions

Legal solutions

Dr. Faisal Abdulrahman Ali Taha proposes two legal solutions for Sudan’s border dispute with Ethiopia. Firstly, to clarify the legal status of al-Fashaga, Taha proposes the revival, development and updating of a Sudanese law to develop al-Fashaga issued in 1971. Secondly, Taha calls for the formation of a fact-finding committee at the highest possible level, with all relevant civil and statutory bodies represented, to find out how “[al-Fashaga] fell into foreign hands so smoothly” and “which party or parties are responsible for the loss with so much indifference” (al-Rakoba, 14 January).

Cooperation between Sudan and Ethiopia

Al-Tahir Satti, the editor-in-chief of al-Saiha (19 December) newspaper, suggests that the Sudanese government reach with Ethiopia a final border settlement agreement that would enable the region to be turned into a hub for joint venture enterprises that benefits the resident border communities in both countries – similar to that in Omm Dagog district on Sudan’s border with the Central African Republic, whereby “the mixed tribal population exchange benefits and share cultivation and pastoral lands across the border without any friction or sensitivities”.

Blocking ports in the east of Sudan and a strong government presence

Condemning the killing of six women and a child by Ethiopian militiamen, the Sudanese Women’s Union called on the government to extend its authority in the border areas and protect its citizens, especially women. They demanded that the government reach a radical solution for the turmoil and the block ports in the east of Sudan (Radio Dabanga, 13 January).

Encouraging a formal Ethiopian apology

Columnist Sabah Mohamed al-Hassan suggests that the Sudanese government strongly responds to Ethiopia to encourage formal apology, describing the encroachment of an Ethiopian military plane on the Sudanese border as a “dangerous and unjustified escalation”. To avoid a war, al-Hassan calls for Sudan and Ethiopia to “work hard” to diplomatically resolve the issue (al-Jareeda, 14 January).