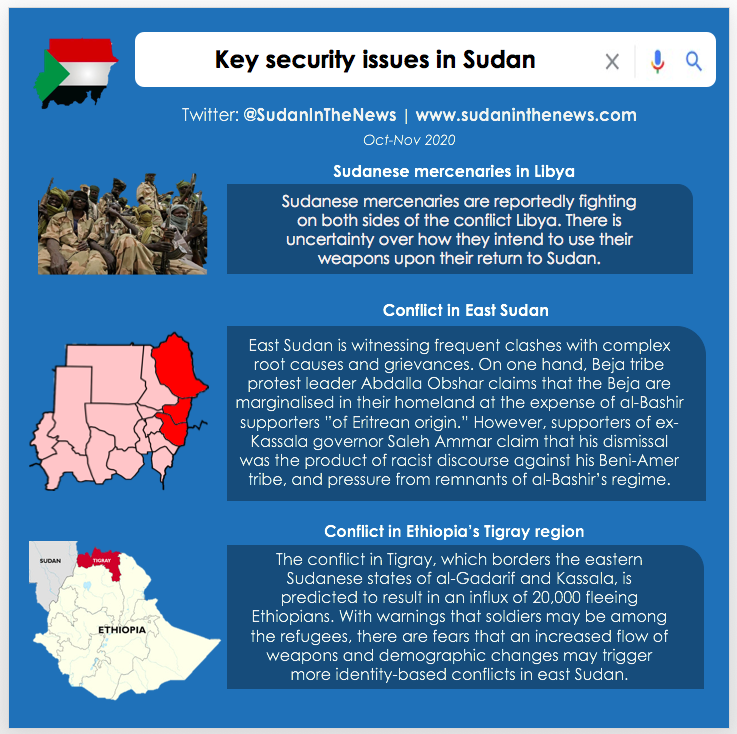

SECURITY BRIEFING: Mercenaries in Libya, East Sudan violence, Juba peace agreement and secularism

In the West of Sudan, there are concerns over how mercenaries fighting in Libya intend to use their weapons upon their return. In East Sudan, Prime Minister Hamdok’s sacking Saleh Ammar as the governor of Kassala has triggered another round of clashes between Beja and Beni Amer groups. In addition, conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region is expected to pose a security threat to Sudan’s eastern borders with Ethiopia. Meanwhile, informal discussions in Juba between the government and SPLM-N al-Hilu on the prospect of a secular Sudan initially seemed promising for the latter, although the government later rejected the recommendations of the Juba workshop.

Mercenaries in Libya

The African Centre for Peace and Justice Studies (27 October) argue that peace cannot be established in Sudan as long as Sudanese mercenaries are in Libya acquiring military weapons amid uncertainty over how they intend to use them when they return to Sudan.

East Sudan

Fighting continues to erupt in East Sudan. Protests temporarily ended and Red Sea State oil facilities were re-opened, although grievances between Beja-speaking and Tigre-speaking tribal groups remain. Abdalla Obshar, a Beja intellectual and organiser of protests in Port Sudan, alleged that supporters of ousted president al-Bashir “of Eritrean origin” were using the Juba peace agreement to take over their land. Obshar claims that Eastern Sudan track representatives in Sudan’s peace negotiations are aiming to “change the demography of the Beja area…have no historical or geographical ties to eastern Sudan and do not speak the Beja language” (Voice of America, 7 October).

Kassala governor Saleh Ammar, a Beni Amer tribesman whose appointment triggered protests from Beja groups, had proposed an initiative to achieve peace and social coexistence in eastern Sudan, even inviting a dialogue with Sayed Tirik, Chairman of the Beja Nazir Council and Nazir of the Beja Hadendawa clan, who led opposition to Ammar’s appointment (Radio Dabanga, 9 October).

However, Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok finally dismissed Ammar after months of objections. The Beni Amer Youth Association blocked roads in response to Hamdok’s decision, with the Chief Nazir of the Beni Amer, Ali Diglel, saying Ammar’s dismissal is “shameful, because the campaign calling for his removal is based on racist arguments, distrust, and the slandering of our identity” (Radio Dabanga, 14 October).

The aftermath of Ammar’s dismissal saw eight killed in clashes between his supporters and opponents in the Red Sea states of Suakin and Port Sudan. He said he considers the decision to remove him from his post “as a surrender to the blackmailing of a group of remnants of [al-Bashir’s regime],” further accusing “corrupt stakeholders” of being behind “the group that fuelled discord and triggered tribal clashes by using a racist discourse and acts of chaos” (Multiple sources, 15 October). In Kassala, another eight, including a member of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) were killed, and 31 were wounded, after security forces dispersed a demonstration by Ammar’s supporters (Radio Dabanga, 16 October).

It is worth noting, however, that the tribal nature of the conflicts is disputed. In a strong condemnation, the Revolutionary Alliance for Eastern Sudan accused the government of fuelling the conflict in the region by “irresponsible interference”, and treating the conflicts as tribal (Radio Dabanga, 12 November).

Nonetheless, the demography of eastern Sudan is likely to change again amid ongoing violence in neighbouring Ethiopia. Al-Gadarif and Kassala are likely to receive tens of thousands of refugees from Ethiopia, amid conflict in the Tigray region that borders the eastern Sudanese states. The Governor of al-Gedaref, Suleiman Ali, said: “within days we will be dealing with more than 20,000 refugees, a number that exceeds the current capabilities of the state”. Indeed, the Kassala Commissioner of Refugees, Khaled Mahmoud, stressed the importance of the security examination due to the presence of soldiers among the Ethiopian refugees (Radio Dabanga, 12 November).

In an analysis of the impact of Ethiopia’s Tigray conflict on Sudan, Cameron Hudson, senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, argues that “the significant influx of weapons, fighters, and refugees to [East Sudan] may unleash substantial new tensions that Sudan’s transitional government has already been proven ill-equipped to handle” (Atlantic Council, 11 November).

Juba peace developments

The Juba Peace Agreement has been incorporated into Sudan’s constitution government, meaning that three seats - occupied by rebel movements - will be added to the Sovereign Council, now existing of 11 members (five military and six civilians) (Radio Dabanga, 19 October). However, the Confederation of Sudanese Civil Society Organisations had called for the incorporation of the Juba Peace Agreement into the Constitution to be halted in order to create an “environment of inclusion,” and that constitutional amendments should be approved by a legislative authority (Radio Dabanga, 17 October).

Furthermore, contentions around the separation of religion from the state in Sudan remain.

The government began the first round of informal discussions on issues including separation of state and religion with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North faction of Abdelaziz al-Hilu (SPLM-N al-Hilu) (Multiple sources, 30 October).

However, the head of the Sudanese government delegation, Lt Gen Shams al-Din Kabbashi, rejected the recommendations of the workshop on the relationship between state and religion. According to Kuku Jagdoul, the official spokesperson for the SPLM-N al-Hilu negotiation team, the parties initially agreed that Turkish model of secularism is most applicable to Sudan, before the government later voiced objections (Multiple sources, 3 November).

Kabbashi later clarified that the government rejected the recommendations in line with Sudan’s Higher Peace Council, which is chaired by the official head of state, Abdulfattah al-Burhan. Indeed, the Hamdok-Hilu agreement that preceded the SPLM-N secularism workshop stipulated that SPLM-N al-Hilu retains the right to self-determination until separation between religion and state are actualised (Sudan Tribune, 9 November).

Solutions

A new national security strategy

Luka Biong D. Kuol, the Acting Dean at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS) at US National Defense University, suggests that Sudan’s needs a national security strategy which clearly defines Sudan’s threats and the force structure needed for such security, thereby providing a new doctrine that would instil a national identity, ethos, and command and control structure that can avoid a fractured security apparatus (Sudan Tribune, 5 November).

Community Cooperation in Security Sector Reform – Kuol also suggests that the conventional disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration (DDR) process must be adapted to Sudan’s uniquely complex conflict dynamics – with reintegration requiring close cooperation with communities over an extended period of time (Sudan Tribune, 5 November).

Dealing with Mercenaries - ACPJS ((27 October) call on Sudanese authorities to launch a disarmament campaign and embark on strong rehabilitation process for people from conflict areas, alongside addressing unemployment to avoid people thinking the war is an option to make money. ACJPS further call on authorities to enact strong law against mercenaries and fully implement it in collaboration with the government of Libya.

Inclusion of civil society in security sector reform - Kuol also emphasises the important role that can be played by civil society in the security sector reform process, “if their understanding is enhanced” (Sudan Tribune, 5 November).

Intervention in East Sudan -The Revolutionary Alliance for Eastern Sudan called on the international community to intervene to stop what they described as ethnic cleansing in eastern Sudan (Radio Dabanga, 12 November).

Mediating the Tigray conflict - Cameron Hudson, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, suggests that Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok “has some political capital to spend” in mediating the Tigray conflict. Citing Hamdok’s chairing of East Africa’s regional Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), Hudson argues that Hamdok “is positioned to marshal the often-underutilized mediation and peace-making resources of IGAD.” Hudson also notes that Hamdok may utilise his participation in the ongoing negotiations over Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance dam “as an important buffer …between Egypt and Ethiopia” to seek to find common ground on issues “striking at the heart of Ethiopia’s national security interests” (Atlantic Council, 11 November).