Report: The New Sudan

The New Sudan

Part 1: Who will lead the new Sudan, and what reforms have been proposed?

Part 2: What are the challenges facing the development of the new Sudan?

Part 3: What solutions have been proposed for the new Sudan to succeed?

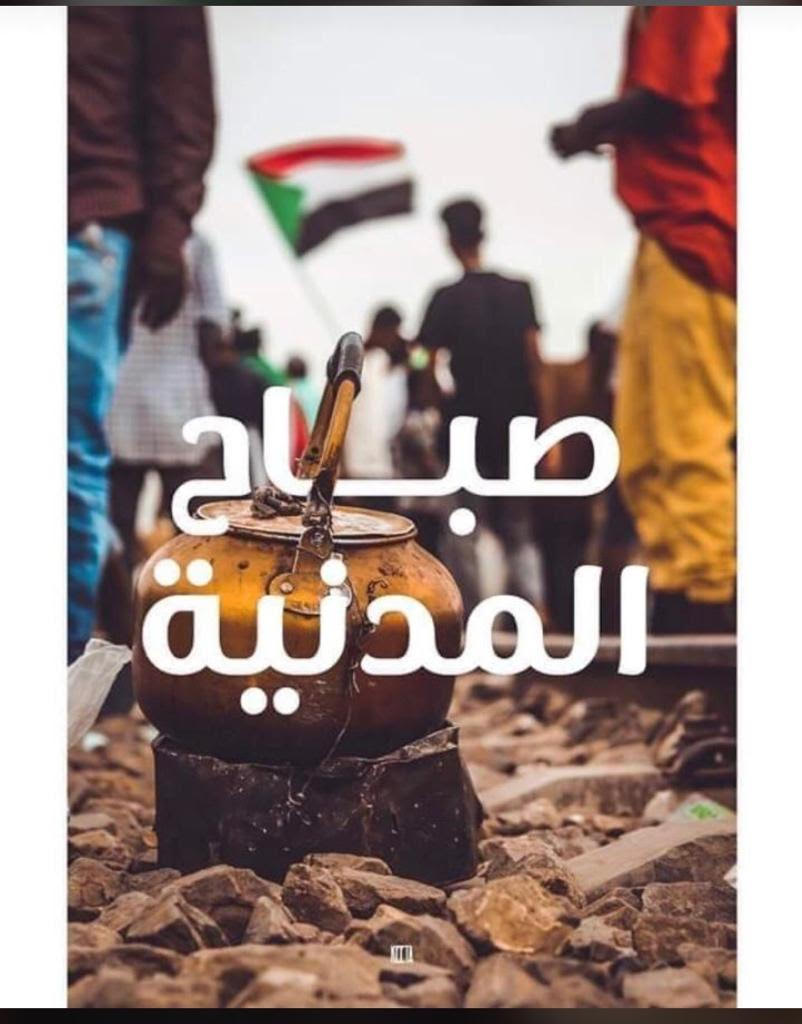

Morning of the Civilian (government).

PART ONE: WHO WILL LEAD THE NEW SUDAN?

On August 17, Sudan’s main opposition coalition – the Forces of Freedom and Change – and the ruling military council sealed a power-sharing deal that allows for a transitional government and elections. (Multiple sources).

Sudanese columnist Nesrine Malik wrote that the agreement reflects the opening of “windows of political change” (Guardian, August 16).

Nonetheless, Malik concedes that in Sudan, “piecemeal erosion followed by rebuilding,” is likelier than revolution, given that Al Bashir’s regime was replaced by the military council that “stood in the shadows behind him.”

So, how will power be divided in the New Sudan? A sovereign council will now take over from the transitional military council, and a new prime minister has been appointed.

Sovereign Council members from Right to Left: Himedti, Hassan Sheikh Idriss, Ibrahim Gabir, Rajaa Nicolas Issa, Shamseldin Kabbashi, Dr. Aisha Musa, Mohammed Elfaki Suleiman, Yassir Al-Atta, Siddig Tawer Kafi. Abdulfattah Al Burhan has his back turned to the camera.

I. Sovereign Council – military representation:

The military council takes up 5 of the 11 seats in the sovereign council that will rule Sudan.

Top general Abdulfattah Al Burhan was sworn in as the leader of the sovereign council (Multiple sources, August 21).

The remaining military seniority to join Al Burhan in the sovereign council are:

· Himedti: The ex-deputy chief of the transitional military council (TMC) and leader of the Rapid Support Forces accused of responsibility for the June 3 massacre.

· Shamseldin Kabbashi: The media face of the TMC, who was the deputy commander of the Sudanese ground forces.

· Yassir Al-Atta: Said to have good relations with the Sudanese opposition, Al-Atta took leadership of Sudan’s ground forces after Al Burhan took leadership of the military council.

· Ibrahim Gabir: The former commander of the Sudanese Navy, Gabir was appointed the head of the TMC’s economic committee.

II. Sovereign Council – civilian representation: (Sudan In The News).

· Mohammed Hassan Al-Taishi: A Darfur-born former member of the Umma Party (led by Sadig Al-Mahdi), who was nominated by the Sudan Professionals Association.

· Dr Aisha Musa Al-Saeed: The 70-year old linguistics teacher is a prominent women leader in Sudan.

· Mohammed Elfaki Suliman: The youngest member of the council (aged 40), he is a journalist who published a political book called: ‘Building the Sudanese state.” He is said to be affiliated to Sudan’s Unionist Alliance.

· Hassan Sheikh Mohammed Idris: The 80-year old lawyer has a wealth of experience of working in Sudanese state institutions – including as a member of parliament in the 80s. Formerly a leading member of the National Umma Party, he previously served as the Minister of Housing.

· Professor Siddig Tawer Kafi: A leading member of the Arab Baathist Party, Tawer is a renowned physics professor, with a considerable background consulting on Sudan’s mining industry and preparing investment maps for Sudanese Conflict Zones.

And finally,

· Rajaa Nicolas Issa: The Coptic Christian legal expert who became legal counsel at Sudan’s Ministry of Justice was jointly picked by the military and the FFC.

III. The new Prime Minister: Abdulla Hamdok

Sudan’s new prime minister is the seasoned economist Abdulla Hamdok, who was most recently the deputy executive secretary of the UN's Economic Commission for Africa. When he worked for the African Development and Trade Bank, Hamdok is credited with shaping policies that spurred Ethiopia's rapid economic growth (Multiple sources, August 21).

Hamdok’s appointment has been welcomed by international and domestic political forces (Multiple sources, August 21).

Amjed Farid, a Sudan Professionals Association spokesman, noted Hamdok’s “track record and achievement” and said that he “has enough popularity and peoples’ support to implement the very difficult emergency plans needed to rescue Sudan.”

The US, UK and Norway troika said Hamdok’s appointment: “presents an opportunity to rebuild a stable economy and create a government that respects human rights and personal freedoms.”

Abdulla Hamdok

IV. Hamdok’s reform plans

Hamdok asserted that the government’s top priorities are to “stop the war, build sustainable peace, address the severe economic crisis and build a balanced foreign policy" (Multiple sources, August 21).

In his first interviews with foreign media (Multiple sources, August 24), Hamdok declared that:

· Sudan requires $8 billion in foreign aid for the next two years to cover its import bills and regain trust in its currency.

· $2billion in foreign deposits is needed to stop Sudan’s pound from falling further.

· Negotiations with the USA to remove Sudan’s terror-sponsor designation are underway.

· “There won’t be a forced prescription from the IMF or the World Bank,” and “the people” will decide on the controversial matters of government subsidies for bread, fuel, electricity and medicine.

· To make Sudan’s economy productive declared an intention to stop exporting products like livestock and agriculture as raw materials: “we will aim to process [them] to create added value.”

· “Stopping war, which represents 70% of the expenditure…will create a surplus that can be invested in production, agriculture and livestock.”

Stopping the war will be easier said than done, according to US Congressman Jim McGovern, who told AFP that he has “grave concerns…about whether military and political officials associated with the former regime will prove trustworthy partners given their history of violence, repression, corruption and bad faith” (August 21).

This leads us to the challenges facing the development of the new Sudan.

PART TWO: CHALLENGES OF THE NEW SUDAN

Securing peace (and solving Sudan’s economic challenges) are an obstacle because the remnants of Al Bashir’s security apparatus remain in power. Furthermore, the public disputes between the FFC opposition coalition and Sudanese rebel movements also impede securing peace. The FFC also continues to be plagued by accusations that it excludes women and Sudan’s non-Arab ethnic groups.

1. Al Bashir’s regime remains

The euphoria of Sudan’s power-sharing deal was tempered by the “tough compromises” which ensured that Al Bashir’s allies retain their grip on power (Multiple sources, August 17).

Symbolically, Himedti - formerly “al-Bashir’s former right hand man in the bloody Darfur conflict” – signed the power-sharing agreement on the military council’s behalf (CNN, August 17). Indeed, Himedti’s appointment to sovereign council is particularly worrying,” given his leadership of the Rapid Support Forces that “led [the June 3 massacre]” (Economist, August 22).

In addition, there is public anger that ex-president Al Bashir, currently on trial for corruption, will not be held to account for the long-list of innocent civilians and casualties under his leadership. It was speculated that worst punishment Al Bashir will face is a fine (Guardian, August 18).

Suliman Baldo, a senior researcher with the Enough Project, told AP (August 17) the survival of the elements of the former regime in the institutions of the transition are an obstacle to Sudan’s democratic transition and sound governance.

Former president Omar Al Bashir in court facing a corruption trial

2. The remnants of Al Bashir’s increase Sudan’s economic challenges too.

John Prendergast of the Sentry, an investigative group that tracks the proceeds of war crimes in Africa, told the New York Times (August 17) that “the companies [the military] control are looting Sudan’s resources and budget for their personal enrichment.”

The power-sharing deal keeps the military in control of the defence and interior ministries “which have large budgets and were responsible for past abuses.” The military - which has allegedly bought off its opponents – worries that reform will lead to accountability (Economist, August 22).

The military’s economic power also leaves them poised to exploit divides among Sudan’s opposition. The International Crisis Group told the Economist: “given the junta’s desire to divide and rule, the civilian opposition cannot afford to be seen as excluding the rebels from the transition.”

3. Unhappy Sudanese rebels

The public spat between the Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF) and the FFC is reflected in SRF spokesman Mohammed Zakari labelling the consultation meeting between the parties in Cairo as a “public relations excerise.” The SRF views securing peace in Sudan as a priority, and questions the FFC’s ability to fulfil it. (Sudan Tribune, August 11).

The FFC reportedly rejected the SRF’s demand to be represented in the sovereign council, saying that it rejects the principle of quotas. (Sudan Tribune, August 13).

Although Sudan expert Gill Lusk attributes the FFC’s issues with the SRF to the FFC’s weak political strategy skills, Rebecca Tinsley writes that the omission of the SRF’s insistence peace in Sudan’s conflict-ridden peripheries is prioritised in the power-sharing agreement “breeds suspicion that the provincials were being sidelined once more” (Open Democracy, August 15).

4. FFC excluding ethnic groups (Open Democracy, August 15).

With the FFC being seen as a Khartoum Arab-elitist movement, Niemat Ahmadi of the Darfur Women’s Action Group said: “elites in Khartoum are still repeating the exclusive approach that has divided the people of Sudan…and led to genocide in Darfur.”

Maddy Crowther, of the NGO Waging Peace, argued: “the agreement between the civilian and military delegations is welcome, [but] there is a danger it just becomes power-sharing between Nile elites.”

To compound matters, concerns about the FFC’s exclusion of women remain rife.

5. FFC excludes women

CNN (August 17) drew attention to the absence of women from the power-sharing signing ceremony, despite playing “a crucial role in the protest movement.”

In fact, the only female speaker was the host, which woman activist Rabah Sadeq labelled “a slap in our face” (AFP, August 24).

Samahir el-Mubarak, a Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) spokeswoman, attributed women’s absence in Sudanese institutions broadly to “the organizations and political parties that are active in the transition [always excluding] women. (AFP, August 24).

SPA member Sarah Abdulgalil called for a debate on finding ways to integrate women, adding that political parties lacked trust. (AFP, August 24).

PART THREE: SOLUTIONS FOR THE NEW SUDAN

A broad range of solutions have been proposed to solve the challenges facing the development of a new Sudan.

1. For legal reforms

To ensure that Omar Al Bashir and his allies will face more serious charges for their crimes, Abdullah Galley, member of the Democratic Coalition for Lawyers, said “we are just waiting for a proper justice minister and a new attorney general.” (Guardian, August 18).

2. For youth leadership

For Sudan to achieve its full potential, Sudanese author Jamal Mahjoub (New York Times, August 22) argues that Sudan’s future lies with the young – calling for Sudan’s old guard to step aside.

Mahjoub suggests that failure to reform Sudan’s system of governance and economy would crush the hopes of Sudanese youth, leaving Sudan “heading toward possible disintegration, economic and political instability, regional conflict and the untold suffering of millions.”

3. For the FFC to deal with its representation issues:

Both the Financial Times editorial board (August 15) and former UK ambassador to Sudan, Dame Rosalind Marsden (Chatham House, August 8) called for the FFC to guarantee the representation of women, youth and persecuted minorities.

In Marsden’s case, she emphasised the need “to transform established patterns of power and privilege.”

4. For the FFC to compromise with rebels:

In the interests of maintain a balance between the urban Sudanese who dominate the FFC, and Sudanese from the conflict zones and peripheries, Marsden called for the FFC to compromise with the rebels – noting that urban Sudanese prioritise civic rights, whereas the peripheral Sudanese priorities peace and political inclusion.

5. For security sector reforms

An example of an FFC compromise with the rebels would be to integrate the SRF into a “professional” army that represents all Sudanese communities as part of an “agenda of peace.” This solution was suggested by SRF senior leader Yassir Arman, who insisted that democracy or sustainable development are unattainable unless issues of war and the security arrangement are resolved (AP, August 14).

Dame Rosalind Marsden also called for a professional and inclusive army to be established, as well as reducing the powers of the intelligence services, and withdrawing the Rapid Support Forces from law enforcement. Chatham House, August 8).

6. For the international community to monitor the military

Marsden also called for the international community to support the aforementioned security sector reforms – a theme in the solutions proposed for the new Sudan’s development.

Indeed, John Prendergast called for international assistance to Sudan to be coupled with pressure for military reforms, adding that: “if this mafia network isn’t countered in some way, the prospects for peace and democracy are very dim indeed.” (New York Times, August 17).

Suggesting that Sudan’s military rulers are “deeply untrustworthy,” with Himedti in particular possibly impeding Sudan’s democratic transition, the Financial Times editorial board (August 15) called for those with influence among the international community to “make clear they are watching.”

Khalid Al-Baih’s cartoon depicts Omar Al Bashir and Himedti serving as an obstacle in the route towards civilian-led government

7. For another revolution

Sudan Professionals Association members have not hesitated to warn of another revolution, if their goals are not achieved. Sara Abdelgalil told the New York Times (August 17) “we will go back to the street,” if a civilian-led government is not achieved in three years.”

Samahir el-Mubarak warned of another revolution if Sudan’s new transitional bodies continue to exclude women. (AFP, August 24).

8. For the military to compromise

To conclude, in an article which noted how Sudan’s uprising resisted both the June 3 massacre and the internet blackout, Nesrine Malik leaves the military with a binary choice – compromise, or “[sleep] with one eye open all the time in a police state, cursed by insecurity” (Guardian, August 16).