#SudanUprising Report: Build-up to the military coup of 25 October

Summary

In the previous Sudan Uprising report, we covered how various analysts viewed the foiled coup of 21 September as a precursor for an eventual coup, particularly how Sudan’s military leaders blamed it on the performance of the civilian government, in keeping with the history of Sudanese military coups that heralded the end of democratic attempts.

This Sudan Uprising report looks at the events and issues raised in the build-up to the eventual military coup of 25 October 2021. As Sudan’s democratic struggle continues, the proposed solutions may serve as inspiration.

Key Events

The start of October 2021 saw the formation of a breakaway faction of the Forces of Freedom Change (FFC), the coalition that selected the civilian component of the government, by the leaders of Darfuri-based armed movements who defected their allegiance away from civilian revolutionaries, towards the military.

The leaders of the military and armed movements escalated their calls for the civilian government to step down, culminating in their organisation of demonstrations that demanded military rule.

In response, the largest protests since the start of the transitional period were held, as hundreds of thousands took to the streets to demand a civilian-led democratic transition. The protests were to no avail as the coup eventually happened

Key Issues

Public statements made by civilian members of the government in the month of October suggested that they knew it was coming, as they, alongside analysts, questioned the military’s democratic commitment.

The formation of the breakaway FFC faction, the National Accord (FFC-NA), is viewed as a way to split and polarise the pro-democracy movement and pave the way for the return to power of the former regime, particularly given the political ambitions of the FFC-NA’s leaders, and their prior relations with the ousted regime.

The pro-military protests were artificially inflated as people were paid to participate. Anti-democratic forces were also revealed to use their financial resources to win the battle for public opinion online via fake grassroots campaigns.

Nonetheless, there are grievances about the exclusionary tendencies of the mainstream FFC, with democracy advocates criticising civilian political elites were being pre-occupied with pursuing personal career and political ambitions at the expense of the national interest.

Solutions

Proposed solutions included: for civilian politicians to adopt a more confrontation stance towards the military, to attempt to gain public legitimacy and focus on creating transitional institutions. Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok was called upon to form a more inclusive executive government, while the US were called upon to apply pressure on the military.

Events

A breakaway faction of the Forces of Freedom Change (FFC) echoed the military’s calls to dissolve the civilian government, and organised pro-military protests. A travel ban was allegedly imposed upon senior civilian politicians, before the largest pro-democracy demonstration since the transitional began was held.

1. FFC split

The Sudanese political crisis escalated, and the path was paved for the eventual coup after a split in the Forces of Freedom Change, the political coalition comprised of civilian political parties, civil society organisations and armed movements that revolted against Omar al-Bashir’s ousted regime, played a leading role in the Sudan uprising and selected the civilian government.

Sudan Tribune (3 October) reported that 16 political and armed groups signed "the National Consensus Charter for the Unity of the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC)", thereby forming a new faction of the FFC.

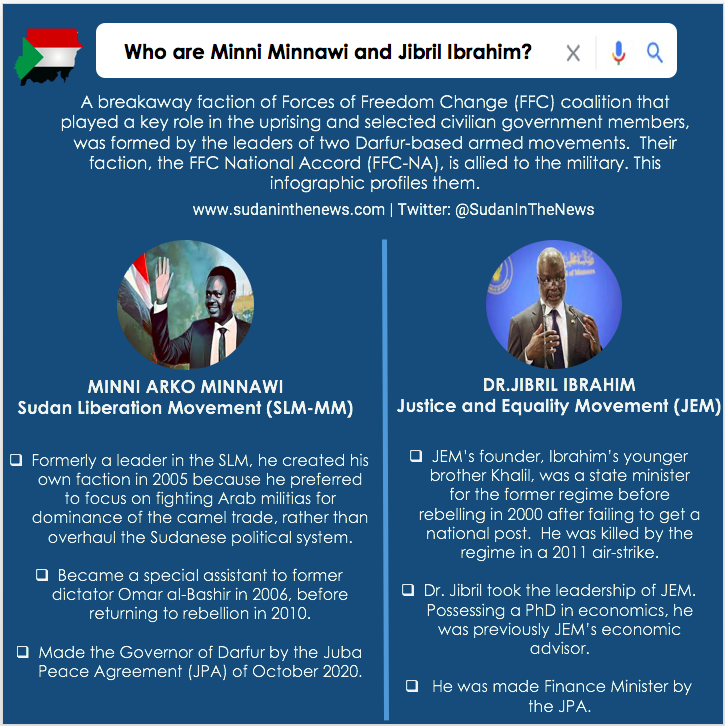

The new alliance – known as the FFC National Accord Group (FFC-NA) - gathers armed movements including: The Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) led by Darfur governor Minni Minnawi, and Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) of Finance Minister Dr. Gibril Ibrahim. In their speeches, Minnawi and Ibrahim denounced the monopoly of power by four components of the FFC saying they have excluded the other groups that participated with them in the struggle against the former regime (Sudan Tribune, 3 October).

Similarly, the head of the ruling Sovereign Council and the commander-in-chief of the Sudanese army, Abdelfattah al-Burhan, echoed the FFC-NA allegations that the FFC monopolises power via four groups that control the Cabinet and impose their partisan agenda. Indeed, the FFC controlled 18 out of Sudan’s 26 government ministries (Sudan Tribune, 3 October).

The FFC-NA then called for the boycott of the mainstream FFC, also known as the FFC Central Council (FFC-CC), until it is reorganised and an agreement is reached on membership representation. Indeed, JEM Political Secretary, Suleiman Sandal, disclosed a request to the Sovereign Council and the Council of Ministers “to stop any political or executive dealings with the FFC-CC, which hijacked the government, until they return to the founding platform” (Sudan Tribune, 8 October).

According to Bloomberg (11 October), the formation of the FFC-NA splinter group “removes a key pillar of support from embattled civilians in the interim government who are increasingly at odds with the military officials they share power with,” a feud that “risks derailing Sudan’s path to democracy”.

Al-Tom Hajo, an FFC-NA member who is the deputy chair of the Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF) coalition of armed movements, said that the FFC-NA leadership demands a government of technocrats, and rejects allegations from the FFC-CC that the FFC-NA breakaway was instigated by the military in an attempt to discredit the government and sow chaos.

Days later, Minnawi demanded the partial dissolution of Sudan’s transitional government and refused to meet with Sudan’s civilian government leaders (Sudan Tribune, 14 October).

The FFC-NA’s boycott of the FFC-CC conforms to the stance of al-Burhan and Himedti, the Sovereign Council deputy chair and the commander-in-chief of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary group. Al-Burhan and Himedti had refused to meet with their civilian sovereign council counterpart Mohamed al-Faki, after the latter’s vocal criticisms of the military component of the government’s threats towards the democratic transition (Sudan Tribune, 4 October).

Al-Burhan would then back up the FFC-NA’s demands for the dissolution of the civilian government.

2. Al-Burhan demands government dissolution

Addressing his soldiers, Radio Dabanga (12 October) reported that Al-Burhan called for the dissolution of the transitional government. "Civilians’ attempts to continue the partnership in its previous form are rejected. There is no solution to the current situation without dissolving the government," he stressed.

Al-Burhan accused civilian political forces of fabricating troubles with the army to distract the public opinion and called for a new "broad-based" cabinet, thereby echoing calls made by the FFC-NA. In response to the calls, Mutaz Saleh of the FFC-CC said that, under Sudan’s constitution, only the FFC has the authority to dissolve the Cabinet (Sudan Tribune, 12 October).

Three days later, Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok rejected al-Burhan and Himedti’s request to dissolve the FFC-majority Cabinet, and form a replacement government involving political groups that form the splinter FFC-NA (Sudan Tribune, 15 October). Instead, Hamdok proposed an alternative solution to the political crisis.

3. Hamdok’s solution

To solve what he labelled as “the worst and most dangerous crisis that not only threatens the transition, but threatens our whole country” (Multiple sources, 16 October), Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok announced a 10-point plan to move past the political crisis that has split the FFC’s civilian and armed components, and escalated tensions between the civilian and military components of the government.

Hamdok said: “the essence of this crisis is the inability to agree on a national project… the conflict is not between civilians and the military, but rather between [revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries],” calling for a de-escalation of tensions and serious dialogue on issues dividing the FFC coalition. To end the frictions that split the FFC, Hamdok proposed broadening the base of the transitional government with more components (Sudan Tribune, 16 October).

4. Travel ban

The crisis between the military and civilian components of Sudan’s transitional government escalated after multiple sources (13 October) reported that the General Intelligence Service (GIS) issued a travel ban for 11 leading civilian members of the Empowerment Removal Committee (ERC)*. Sources reported that the ban issued by the GIS includes member of the Sovereign Council Mohamed al-Faki and Minister of Cabinet Affairs Khaled Omar, who have recently been vocally critical of military threats to the democratic transition.

5. Pro-military protests

In protests organised by the FFC-NA, the political crisis in Sudan’s democratic transition reached a new low after thousands of Sudanese took to the streets of Khartoum to demand the dissolution of the civilian government (Multiple sources, 18 October). Pro-military slogans were chanted including: “one people, one army”, as demonstrators announced they would stage a sit-in until the dissolution of the civilian government (Sudan Tribune, 17 October). Other chants included: “the army will bring us bread” (AFP, 17 October).

In response to the protests, the mainstream FFC-CC said: “the current crisis is not related to dissolution of the government… it is engineered by some parties to overthrow the revolutionary forces ... paving the way for the return of remnants of the previous regime” (AFP, 17 October).

6. Pro-democracy protests

Days later, across Sudan, hundreds of thousands participated in a ‘March of the Millions’ in favour of a civilian-led democratic transition, in what Reuters estimate is the largest protest of Sudan’s democratic transition. Protests took place from Darfur in the West, to Atbara in the White Nile state, and around Khartoum, as well as among the Sudanese diaspora in London, Washington DC, and other western cities (Multiple sources, 21 October).

Issues

The key issues raised include: that the prospect of a coup was increasingly raised by civilian members of the government which indicates the level to which tensions among the military-civilian government were escalating, alongside the military’s aversion to democracy. The formation of the FFC-NA, and its alliance to the military, reflects a threat to the democratic transition that was projected as far back as the time that the transition began, as it polarised the pro-democracy movement and paved the way for the return of the ousted regime. While anti-democratic forces are artificially inflating their support on the street and online, the infighting and mismanagement of the civilian government has also been blamed for inviting the military coup.

The coup was predicted

While the military coup eventually came on 25 October, public statements made by civilian members of the government in the month of October suggested that they knew it was coming.

Madani Abbas Madani, an FFC member and former Trade minister, spoke about a planned coup by the military and allies: “[Al-Burhan and his deputy Himedti] are circumventing the Constitutional Document…they do not want to reform the military and security sector and establish a unified army," Madani stressed, adding that civilians should focus on achieving democratic reforms rather than being distracted by internal disputes (Sudan Tribune, 3 October).

Five days later, Madani told Reuters (8 October) that the military attacks on civilians in the wake of the “foiled” coup of 21 September reflected that: the “military component is not keen on democratic transition…they aim, by weakening the civilian authority through economic sabotage and encouraging ethnic protests ... to create a reality that allows them ... to take control of Sudan”.

Siddiq Tawer, a civilian member of the Sovereign Council, also hinted at the possibility of a coup following the reactions of the military leaders to the 21 September foiled coup, including the refusal of Al-Burhan and Himedti, the chair and deputy chairs of the Sovereign Council respectively, to have any meetings with civilian Sovereign Council member Mohammed al-Faki. Tawer slammed military leaders al-Burhan and Himedti for suspending the council’s meetings, as well as arguing that al-Burhan’s comments that the military are the “guardians of the revolution” come from “those with a putschist mentality", adding that the military leaders must be convinced to abide by what is stipulated in the Constitutional Document” (Sudan Tribune, 4 October).

Indeed, al-Faki himself alleged that al-Burhan aims to “create a new civilian government that he can control”, by installing allies inside the civilian government under the guise of expanding political representation. Al-Faki added that al-Burhan believes now is the time to strike because of the fatigue and apathy of the Sudanese people over the tough economic situation and political infighting (Axios, 20 October). The military coup was staged only five days later.

But, before that, were the pro-military protests. Following the demonstrations against the civilian government organised by the FFC-NA, Ja’far Hassan, a spokesperson for the FFC-CC, called the pro-military sit-in “an episode in the scenario of a coup d’etat”. Hassan said the protests aimed “to block the road to democracy because the participants in this sit-in are supporters of the former regime and foreign parties whose interests have been affected by the revolution” (AFP, 17 October).

Suspicions that the coup was coming only amplified pre-existing scepticism around the military’s democratic commitment.

2. Military aversion to democracy

The military worries about democratic transition as it may be subject to justice for abuses committed, and may lose their dominant and privileged place in the Sudanese economy, argues the International Crisis Group’s Jonas Horner (Independent, 19 October).

Indeed, al-Burhan alone allegedly controls the security services and economic military companies, including "10 billion-dollar companies…around the world that manage slaughterhouses and export meat,” according to Ibrahim al-Sheikh, the Minister of Industry and a leading FFC-CC member, who responded to al-Burhan’s claims that the FFC-CC monopolises power via four groups that control the Cabinet and impose their partisan agenda (Sudan Tribune, 3 October).

Furthermore, al-Faki accused al-Burhan and the military of forestalling reforms of state institutions — including the civil service, judiciary and security sector — which, he said, were essential for dismantling the "old state" and transitioning to democracy (Axios, 20 October).

3. The formation of the FFC-NA

The leaders of Darfur-based armed movements forming an allegiance with the military forms a threat to the democratic transition that was projected as far back as the time that the transition began. Thus, the formation of the FFC-NA was viewed as a way to polarise the pro-democracy movement and pave the way for the return to power of the former regime.

Back in 9 July 2019 (Foreign Policy), analyst Jerome Tubiana raised the prospect of Darfuri rebel movements forming a strategic alliance with Himedti, a fellow Darfuri, in an alliance of Sudan’s marginalised peripheries against the civilian democrat movement dominated by the “riverine elite”, the Arabs of central Sudan.

Then, after the Juba peace agreement that co-opted armed movement leaders into the transitional government, researcher Jean-Baptiste Gallopin warned that Sudan’s democratic prospects will fade if the deal becomes an “instrument for the ambitions of [the armed movements],” also raising the prospect of a coalition of peripheral leaders including Himedti and the Darfur-based armed movements, which would weaken the civilian component of the government comprising of elites from the Centre (War On The Rocks, 22 September).

These projections came true after the breakaway FFC-NA was formed by Minni Minnawi, the leader of the Darfur-based armed Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) and Dr. Jibril Ibrahim, the leader of the Darfur-based Islamist Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), a move that is viewed beneficial to the former regime, which Minnawi and Ibrahim both have a history of intermittently allying with and rebelling against. Indeed, Asmaa Jum’ah, the editor-in-chief of al-Democrati (19 October), argued that Minnawi and Ibrahim’s current alliance with the same military they fought against and blamed for the marginalisation of Darfur, indicates that they are untrustworthy.

Minnawi’s history: Journalist Sabah Mohamed al-Hassan suggested that Minnawi’s move benefits the remnants of Omar al-Bashir’s ousted regime. Al-Hassan wrote that Minnawi is “accustomed to creating rifts and splinter groups wherever he went,” noting that he ceded from his own SLM to become an assistant to former president Omar al-Bashir, who’s forces he led a rebellion against. Thus, for al-Hassan, Islamist remnants hinge their hopes of returning to power on Minnawi “because of his unprincipled, slippery personality and visible intention to destroy the FFC”. Al-Hassan also wrote that the Islamists were happy to hear Minnawi criticise the FFC’s movements against the former regime and its remnants (Al-Jareeda, 3 October).

Asmaa Jum’ah, the editor-in-chief of al-Democrati (19 October), suggests that Minnawi exploited the uprising opportunistically as a platform to support the military’s seizure of power in order to prolong his political relevance

Ibrahim’s history: Writer Buthaina Teriws also labelled the formation of the FFC-NA as a reflection of Islamist attempts to retain power, labelling the Islamist Dr. Jibril Ibrahim “the Muslim Brotherhood’s minister” (al-Rakoba, 18 October). Asmaa Jum’ah suggested that – Ibrahim – an Islamist allied to the former regime until rebelling against it “because he was not given positions” – is allegedly trying to revive the Islamists’ dominance of Sudan, under his leadership (al-Democrati, 19 October).

The FFC-NA under Minnawi and Ibrahim’s leadership would then go on to organise protests against the civilian government, although reports suggest that the participant figures were artificially inflated with cash incentives.

4. Fake pro-military protests

Evidence circulated social media that members of the public were paid to participate in the protests calling for the military to take power.

In videos posted by activists, young demonstrators spoke about receiving money for their participation in the pro-military protests. Heads of Islamic schools are accused of being paid to send students to participate in demonstrations, in a violation of international treaties (Sudan Tribune, 17 October).

Osman Mirghani, editor-in-chief of al-Tayyar newspaper, said the pro-military demonstration is reminiscent of the practices of the former regime, which bribed people to participate in pro—regime protests (Sudan Tribune, 17 October). Buthaina Terwis expressed similar sentiments in al-Rakoba (18 October), alleging that the military component of the government “generously pays money for demonstrations and political crowds to support its plans”.

Furthermore, having noted that children were paid to participate in the FFC-NA’s protests at a time when the Sudanese school day has been reduced to four hours due to bread shortages, Terwis argues that it is the “proven habit of Islamists to exploit the needs of the poor and violating the rights of children [who have] been used as cheap ends in political machinations”.

5. The information war

The military components and the opponents of democracy have also used their financial resources to artificially inflate their support online, through the usage of astroturfing campaigns (fake grassroots efforts that primarily focus on influencing public opinion).

With much of the Sudanese battle for public opinion occurring online, Reuters (19 October) note that the 30% of Sudanese with internet access “depend heavily on social media for news, in a report that Facebook closed two large networks targeting Sudanese users linked to the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and supporters of the former regime agitating for a military takeover.

In both networks, posts mimicked news media but offered skewed coverage of political events. The Sudanese Information ministry said former regime loyalists were “working systematically to undermine the transition and tarnish the image of the government”. Representatives of Valent Projects, a firm contracted by the ministry to find the networks, said the networks were “agitating for a military takeover [amid pro-military protests], and in the aftermath of the coup attempt,” as they try to give the impression of grassroots support for anti-civilian protests.

Nonetheless, despite the artificial inflation of anti-democratic or anti-civilian sentiments, they still exist in the form of grievances against the civilian government.

6. Grievances against the civilian government

Participants in the pro-military protests expressed several grievances with the civilian component of the government, namely: their exclusionary tendencies and neglect of the marginalised peripheries.

Some protesters complained that that the government overlooked other states beyond Khartoum (AFP, 17 October). Meanwhile, protester Ibrahim Ishaaq said the government is dominated by only four political parties, and Sudan will never have stable government if a small group makes decisions. Similarly, protester Muhiddeen Adam, a member of Minnawi’s SLM faction, said: “few political forces want to drive [Sudanese] policy by the same policies of the previous administration… and these policies will never take us anywhere" (Voice of America, 18 October).

Thus, as BBC Africa analyst Magdi Abdelhadi noted, the demonstrations were not solely pro-army, but also featured those accusing the [FFC-CC] excluding other groups from the transition (BBC, 20 October). Indeed, grievances towards the performance of the civilian government were also head by democratic advocates, who warned that the civilian political parties are repeating the same historic mistakes that caused the failure of Sudan’s previous democratic transitions.

7. The same historical mistakes / The performance of civilian government

Sudan’s previous democratic attempts, which followed the civilian uprisings of 1964 and 1985, both lasted less than five years, after they failed for the same reasons: a broad-based coalition of civilian political parties failed to develop solutions for Sudan’s complex problems, as they were pre-occupied with infighting, thereby inviting the military to take power under the guise of restoring order (Sudan In The News, 12 August).

Indeed, Abdelhadi argues that a fundamental flaw of Sudan’s political class since independence in 1956 is: “the tendency to fragment and splinter…failure to compromise and build consensus paved the way for the military to step in, to mount coups under the pretext of rescuing the country from the chaos inflicted upon it by politicians” (BBC, 20 October).

The repeat of history is happening today. Yezid Sayigh of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace noted that the military shifted to more assertive approach to dealing with civilian political parties after the latter proved disunited (Independent, 19 October), with Reuters’ (8 October) military source blaming the political crisis on civilian politicking and mismanagement, saying: “the root of the problem is the divergence of the parties that are controlling the FFC from the transitional constitution by monopolizing power”.

Wael Mahjoub, a pro-democracy writer, also blamed the crisis facing Sudan’s democratic transition on the FFC-CC, suggesting that it has become a club for the career advancement opportunities and party quotas. Mahjoub blames the FFC-CC for the military’s growing threats to the democratic transition, citing its: weakness, inaction, poor choice of officials, concessions, gasping for positions and infighting (al-Rakoba, 14 October).

Similarly, Sabah Mohammed al-Hassan argued that the civilian government’s weakness, silence, concessions and “turning a blind eye” to their legitimate and guaranteed rights encourage the military to threaten the democratic transition (al-Rakoba, 14 October).

Solutions

Proposed solutions directed at civilian politicians included: a more confrontation stance towards the military, attempts to mend their relationships with the street, and to create transitional institutions, with Hamdok called upon to reshuffle his Cabinet. The US were called upon to apply pressure on the military to support the democratic transition.

Confrontational stance

Sabah Mohamed al-Hassan called for the civilian government to adopt a more confrontational approach towards the military component of the government, by making strong decisions that deter the military component, thereby restoring its revolutionary standing. Arguing that “passive silence will achieve nothing but humiliation,” she credits civilian sovereign council member Mohammed al-Faki’s confrontational stance for igniting anger in army commander-in-chief, and Sovereign Council chairman, Lt. Gen al-Burhan - “until he reached a point of bankruptcy” (al-Jareeda, 14 October).

2. Hamdok cabinet re-shuffle

On the day that pro-military protesters held demonstrations against a civilian government “facing a growing crisis that could topple its rule”, analyst Hassan Ali called for Prime Minister Hamdok to deal with the grievances by partly reshuffling his Cabinet or expand the number of ministers, alongside setting a timetable for the composition of the legislative assembly and taking steps toward organising a general election (Voice of America, 18 October).

3. Reforms of institutions

Political analyst Dr. al-Shafee’ Khidr argued that the political and social polarisation may lead Sudan to a situation of civil war as in Syria, Yemen and Libya. Thus, Dr. Khidr proposed solutions including: reducing the Sovereign Council to five or six members, reviewing the performance of all council members, forming a Cabinet of professional competencies rather than partisan or regional quotas, reforming the justice system and civil service appointments, the investigation of accusations against the anti-corruption committee retrieving the assets of the former regime, the immediate formation of independent national commissions, with priority given to the commissions of constitution-making, the constitutional conference, and elections.

The national commissions, in addition to fulfilling their well-known tasks, will also achieve widening participation in the transitional and state administration bodies, Dr. Khidr suggested (al-Quds,18 October).

4. Mending civilian politicians’ relationship with the street

Arguing that the crisis facing Sudan’s democratic transition is the inevitable result of the inaction of the Forces of Freedom and Change Central Council (FFC-CC), Wael Mahjoub calls for the FFC-CC to “solve their problems with the neglected streets,” through transparency, practising the virtue of self-criticism and holding accountable its cadres who caused the “political collapse”. To resist military coup attempts, Mahjoub concludes with calls for the mass movement to reorganise itself through a new alliance of revolutionary forces that is not led by “the same forces whose political and executive practices led to the disappearance of the slogans and goals of the revolution” (al-Rakoba, 14 October).

5. US pressure on the military

Yezid Sayigh of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace said that civilians’ “only possible hope” is “an unambiguous public stance from the US warning against any form of a military takeover and hinting at the possibility of Sudan losing access to the IMF and World Bank etc., could have a huge effect on the Sudanese military’s behaviour” (Independent, 19 October).