#SudanUprising Human Rights report May 2021: developments, issues and solutions

Protesters killed, activists silenced by Cybercrime laws and civil society rejects a controversial new security law

Summary

In developments that reflected Sudan’s limited freedom of expression, two young protesters were killed during a commemoration of the June 3 2019 massacre. Furthermore, the Cybercrime Act is allegedly being used to stifle dissent, with a proposed Security Bill also viewed as attempt to legally restrict freedom of expression. Another legal development saw major judicial changes whereby the chief justice was sacked and the attorney general resigned.

The five issues identified in this briefing include: legal and institutional limits on press freedom and freedom of association, with the Cybercrime Act and draft Security Bill identified as causes for concern. In addition, analysts and legal insiders suggest that Sudan’s judicial system lacks the resources and political will to find justice for protest crackdown victims. Indeed, in an exclusive interview with Newlines Magazine, Nabil Adib, the human rights lawyer who leads the committee to investigate the June 3 2019 massacre, said that Sudan will be “destabilised” if he publishes the committee’s finding.

The five proposed solutions for human rights in Sudan include: the adoption of international standards on freedom of expression and use of force, providing for a transparent justice process, rejecting the security bill and reforming the justice system completely.

Developments

Deadly protest dispersal

Two young men were shot dead and 37 were wounded after army forces dispersed – with live bullets - a group of people commemorating the June 3 2019 Khartoum Massacre (Multiple sources, 12 May). The young men were named as Osman Ahmed and Muddathir al-Mukhtar (Sudan Tribune, 13 May).

Attorney general Tajelsir al-Hibr said the injuries of the two killed protesters “may indicate that the shooting was intentional” (Human Rights Watch, 19 May). However, in a statement, the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) said that “no instructions were issued to the forces protecting the army command to use live ammunition against the people” (Radio Dabanga, 12 May).

Major judicial changes

Musa resignation was preceded by major judicial changes which saw the sacking of chief justice, Niemat Mohamed Abdallah and the resignation of attorney general Tajelsir al-Hibr. Although is unclear why Abdallah was sacked, Sudan Tribune (18 May) note that the decision has been criticised for delaying importing reforms.

Meanwhile, al-Hibr submitted his resignation several times and had recently protested to the Sovereign Council about decisions made by the Empowerment Removal (Tamkeen) Committee that aims to retrieve the assets of the former regime. Al-Hibr was reportedly unhappy that several prosecutors accused of being close to the former regime were removed without his prior consultation,

Draft security bill

An internal security agency bill has been drafted, providing a new security apparatus powers of arrest for 48 hours without a court order or warrant from the Public Prosecution office (Sudan Tribune, 25 April). According to Radio Dabanga (26 April), the bill was proposed by Justice Minister Nasreddin Abdelbari, who said the bill was prepared by a limited-membership committee and will be presented to a group of experts on the rule of law, security and democracy, before embarking on the establishment of broad consultative workshops as part of preparations for presentations to the Cabinet.

Activists charged for “false news”

Activists are being charged in Sudanese courts for spreading “false news” under the Cybercrime Act of 2018. Firstly, human rights activist Khadeeja al-Deweihi was charged under Articles 24 and 25 of the act for a May 13 2020 Facebook post discussing the health situation in Sudan. Al-Deweihi was summoned to appear at the Office of the Prosecutor on December 14 2020, where she was asked about her political affiliation and her engagement with the Communist Party of Sudan (Radio Dabanga, 27 March).

In addition, Orwa al-Sadig, a member of the Tamkeen committee was sued by Sudan’s head of state, Lt. Gen. Abdulfatah al-Burhan and charged with “publishing lies and fake news and committing insults of disrepute” under the Cybercrime Act (Global Voices, 4 March).

Alsadig is under investigation for a solidarity speech he made on behalf of his colleague, Salah Manna, on 6 February 2021.

2. Five human rights issues

Press freedom limits (Radio Dabanga, 4 May)

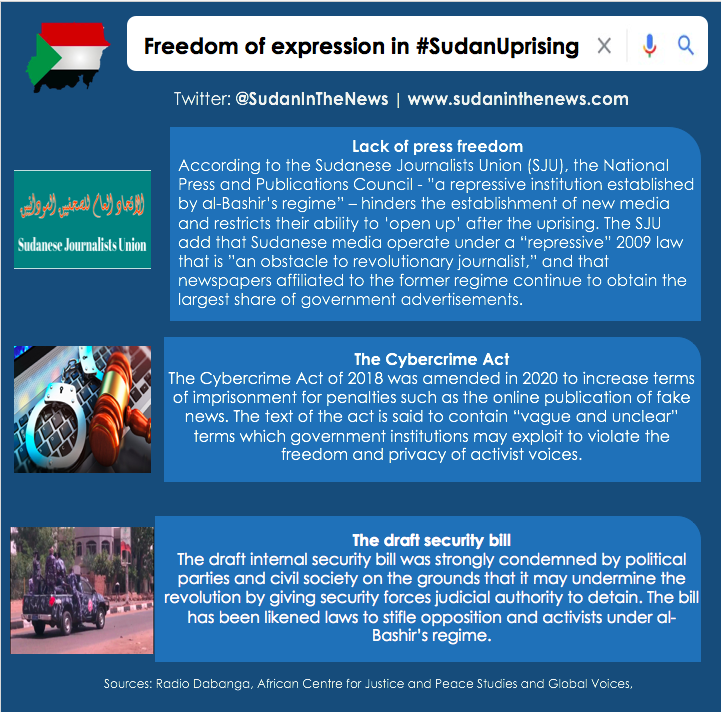

To mark World Press Freedom Day, the Sudanese Journalists Union (SJU) made a statement against the “repression” of journalists in Sudan. The SJU criticised the ongoing operations of the National Press and Publications Council, labelling it “a repressive institution established by the defunct regime”. Radio Dabanga note that the press council oversees the grant of licenses for newspapers, can impose huge fines on publishing houses, and “often hinders the establishment of new newspapers or restricts media outlets’ ability to ‘open up’ since the revolution.”

According to the SJU, Sudanese newspapers still operate under the “repressive” 2009 law that “the former regime put in place to protect itself, silence mouths and deny press freedom”, which the SJU labels “an obstacle to revolutionary journalism”, enables strict state control over the press and journalism with licensing and approval powers, heavy fines, and criminal sanctions for media outlets and journalists.

Finally, the SJU allege that newspapers affiliated to the former regime continue to obtain the largest share of government advertisements.

The Cybercrime Act further limits freedom of expression

Indeed, freedom of expression in Sudan is also legally restricted by the Cybercrime Act of 2018, which the African Centre of Justice and Peace Studies (26 March) state was “designed by al-Bashir’s regime to limit the freedom of activists, bloggers, and media professionals, and was amended in 2020 to increase terms of imprisonment for various penalties including the online publication of false news”.

Furthermore, Khattab Hamad (Global Voices, 4 March) dissected the text of the act, in an exploration as to how it can be abused to limit freedom of expression. Hamad argues that government institutions may violate fundamental freedoms and the privacy of opposition and activist voices through terms that “lack clarity and definition,” such as: national security, prestige of the state, sensitive information and designated authority. Similarly, Ahmed Elsanousi, a lawyer specialising in criminal code and administrative law, suggests that the act “contains vague and unclear terms,” making it easily exploitable

Security bill rejected by civilians

Several civilian stakeholders have strongly condemned the draft internal security bill under the grounds that it may be used to limit freedom. Yasir Arman, the deputy head of Malik Agar’s faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North, said the bill was “as if Omar al-Bashir wrote it from his prison,” referring the former regimes suppression of opposition groups (Sudan Tribune, 25 April).

Similarly, if the law is approved, columnist Yousif al-Sondy questions what the difference would be between Sudan’s civilian leadership - “most of whom suffered the horrors of detention in al-Bashir’s security cells” - and the ousted regime, should the civilians enable the “human rights violations” they accuse the former regime of (al-Tahreer, 24 April).

Sudanese political parties and civil society groups also criticised the internal security bill. Firstly, the Democratic Unionist Alliance, having accused the Ministry of Justice for failing to consult political groups ahead of drafting the bill, criticised its broad immunities, special courts, and the power given to the new security apparatus to withdraw cases from regular courts (Sudan Tribune, 25 April).

In addition, the Sudanese Communist Party said the the law poses a threat to public freedoms and represents a step towards dictatorship, accusing the military component of the Sovereignty Council and the Cabinet of seeking to undermine the revolution (Radio Dabanga, 26 May). The Communists also labelled the law "a new episode of the conspiracy against the forces of the revolution, aiming to circumvent its objectives(Sudan Tribune, 25 April).

Furthermore, the Darfur Bar Association said the law violates the Constitutional Document that stipulates the need to limit the powers of the authorities as it provides security forces a judicial authority to arrest and detain in private guards (Radio Dabanga, 26 May).

The legal system hinders justice for victims of protest crackdowns

Beyond the political limitations preventing justice for those massacred on June 3 2019, Mohamed Osman, Human Rights Watch (12 April) assistant researcher for Africa, cites institutional issues within Sudan’s legal system - a lack of resources and political will - as obstacles to justice.

Osman quotes Mahmoud al-Sheikh, a member of the attorney-general’s committee to investigate abuses, to say: “we are struggling to get the security forces to cooperate including by providing us with access to crucial evidence or accept requests of lifting immunities of suspects”. Furthermore, Osman notes that Sudanese criminal law does not recognise command responsibility as a mode of liability, “which could hinder the possibility of holding mid-to-top level commanders accountable.” This particularly poses a problem for the committee investigating the June 3 2019 massacre.

The risks of finding justice for the June 3 2019 massacre victims

In an interview with Mat Nashed (Newlines Magazine, 5 May), Nabil Adib, the human rights lawyer who leads the committee to investigate the June 3 2019 massacre in Khartoum, said “whatever we decide will destabilise the country”. Although Adib’s committee was meant to deliver its findings by the end of 2019, Nashed raises the prospect of senior security officers in the Military Council trying to overthrow the civilian half of the government and consolidate power if Adib finds them guilty of ordering the massacre. Nonetheless, notes Nashed, “many fear that Adib will reinforce a climate of impunity if he absolves senior military officers from blame”.

3. Five solutions

International law enforcement standards on the use of force

The African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies (ACJPS, 14 May) call for Sudanese authorities to ensure law enforcement agencies comply with international standards on the use of force, “[making it clear] that arbitrary or abusive use of force by security forces will be punished.”

ACJPS specifically suggest that police and other security services policing demonstrations or performing other law enforcement duties receive adequate training and caution on the use of force in line with the UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials and the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials. Furthermore, ACJPS call on Sudanese authorities to refrain from deploying armed forces and government-sponsored militias including Rapid Support Forces to disperse peaceful gatherings

Transparent justice process

To find justice for Sudanese victims of crackdowns on protests, Mohammed Osman, Human Rights Watch (12 April) assistant researcher for Africa calls for a “meaningful” transparent justice process, with the Sudanese government providing “regular public updates on the progress in investigations of public interest and guaranteeing victims and their families effective participation.” Osman argues that while “justice efforts required in Sudan are ambitious and long-term,” the government, with international support, should take “effective, prompt actions to bolster current efforts”.

Committing to international standards on freedom of expression

ACJPS (26 March) call for Sudanese authorities to “respect and guarantee the right to freedom of expression as provided for in article 56 of the Constitutional Declaration and international and regional human rights treaties that Sudan is a state party to,” with law enforcement agencies to be instructed to cease harassing and intimidating individuals exercising their rights legitimately. ACJPS specifically call for the decriminalisation of “false news” and proposes reforms adhering to regional and international standards to which Sudan has committed: the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Similarly, Orwa Alsadig, the activist and member of the Tamkeen committee sued by Lt. Gen. Abdulfattah al-Burhan calls for legal and legislative reform in line with the international bill that guarantees freedom of expression, alongside laws that control media work and combat publishing that incites hate speech (Global Voices, 4 March).

Reformed justice system (Radio Dabanga, 23 May)

In the letter explaining her resignation from the ruling Sovereign Council, Aisha Musa called for a reformed justice system, which is “unattainable by replacing persons only”.

Musa emphasised the need for practical steps around setting laws that guarantee the flow of justice and forming a professional constitutional court capable of preventing transgressions on the constitution, alongside “working strongly towards a constitutional congress that guarantees laying of a permanent democratic constitution”.

In addition, to support a “just” democratic transition, she said that a probe into the delayed publishing of the results of the investigation into the sit-in dispersal massacre (June 3 2019) must be within the priorities of a comprehensive governmental programme for which the yet unestablished justice commission shall be assigned.

Rejecting the security bill (al-Tahreer, 24 April)

Columnist Yousif al-Sondy calls for the civilian government to reject a draft security bill suggesting that the government confines the authorisation to arrest solely to the police and limits the authority of security forces to “the collection and analysis of information and passing it to concerned bodies.” Arguing that revolutionary Sudanese should not tolerate a security that arrests, tortures and kills, al-Sondy concludes that the bill is “wrong” and “its backers should know that it is unlawful at the age of this revolution”.