EXCLUSIVE REPORT: The next Sudanese general election is scheduled for 2022, but are the political parties ready?

Sudan In The News is a youth-led organisation currently developing a project to enhance Sudan’s democratic culture and enhance the political participation of Sudanese youth. For further information on our project and potential partnership opportunities, please contact sudaninthenews@gmail.com

Introduction

Representatives of Sudan’s Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC), a broad coalition that includes political parties currently sharing civilian government positions, want the transitional period to be extended as they claim that the political parties are not ready for elections. This exclusive report finds out why this is the case - with strong signs that more work needs to be done to develop Sudan’s democratic culture by building bridges of understanding between the political parties and a public that does not trust them.

With Sudan’s elections scheduled for 2022 set to herald the end of the transitional period, various well-informed analysts project that military rule in Sudan will be restored, thereby putting the nail on the coffin containing Sudan’s democratic dreams. The foundation of such projections lies on the premise that Sudan’s current uprising is destined to follow the same trajectory of the previous civilian uprisings of 1964 and 1985 – whereby a broad coalition of civilian political parties was unable to govern effectively. Deficient of strategies, visions and solutions to solving Sudan’s problems, on top of an inability to gain legitimacy among the public, the uprisings of 1964 and 1985 eventually saw the military step into the gap created by the civilian politicians within less than five years of the initial uprising.

Sudan In The News’ report set out to conduct research on whether the FFC face the same issues as their counterparts of yesteryear. This report synthesises key events, alongside a range of insights from political experts - particularly within Sudan – which indicate that the FFC’s relationship with the public is strained. In addition, we exclusive spoke to four people – two of whom are formally involved in the FFC, and two politically informed members of the electorate who the FFC parties seek the support of.

Summary

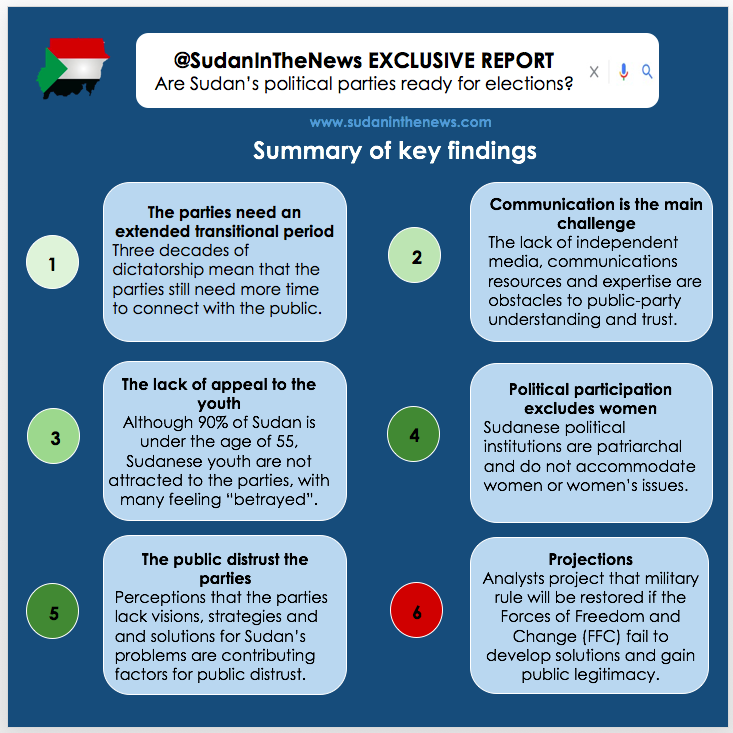

The parties need an extended transitional period: 30 years of Omar al-Bashir’s totalitarian regime prevented the parties from engaging with the public. FFC representatives believe that the transitional period of three years is too short for Sudan to build the democratic culture needed for elections.

The parties are viewed as lacking ideas and solutions: While this has been attributed to the legacy of dictatorship which forced them to prioritise short-term survival rather than long-term policy development, alongside Sudan’s brain drain, sentiments that the parties lack strategies, visions, ideas and solutions are contributing to perceptions that they seek to hold onto power for the sake of it, culminating in distrust towards the parties.

Public distrust towards the parties: Another factor causing distrust towards the parties is Sudan’s limited experience with democracy, and by extension, lack of interpersonal trust on a societal level.

Communication is the main obstacle preventing the parties and the public from understanding each-other: Furthermore, the public and the parties are unable to understand each-other and communicate in a productive matter due to logistical communication issues such as: Sudan’s scarcity of independent media free from government control, alongside the parties’ lack of mass communications expertise and resources, and their continuation of “old-fashioned” communication techniques. In addition, the FFC’s discursive tendency to blame the ousted regime for Sudan’s low standards of living is said to be a “currency of short validity”. All factors contribute to gaps of understanding between the parties and the general public.

Lack of appeal to the youth: Despite Sudan’s youthful demographics, the political parties are not attractive to the youth, who are said to prefer engaging with civil society organisations and Resistance Committees. A young Sudanese respondent noted that many youth feel “betrayed” by the parties.

Political participation excludes women: Sudanese political institutions are said to be patriarchal, sexist and uninviting of women through exclusionary practises that hinder the political participation of women. This is reflected in poor representation for women and the lack of pro-women’s policy production.

The “traditional” sectarian parties are most likely to have electoral success: There is also the belief that the main benefactors of elections in 2022 will be the traditional sectarian parties such as the Umma Party and the Democratic Unionists, who are able to utilise their past experience of mobilising clan and tribal networks. Three respondents noted that such parties and their “religious following” do not build support on the basis of their programmes and visions for solving Sudan’s issues, with one saying that the victory of the traditional parties on the basis of “exchanging favours” contradicts their vision of a democratic Sudan where politics is a battle of “ideas and visions”.

Projections: With all of these factors resulting in the FFC parties’ inability to develop or articulate solutions for Sudan’s problems and thus gain public legitimacy through popularity, analysts project that military rule will be restored – as previously occurred in Sudan’s history.

History of Sudan’s democratic transitions

To help us identify the issues that need to be solved to consolidate democracy during the current democratic transition, it is important to know the history of Sudan’s previous civilian uprisings, the brief democracies that followed them, and the circumstances that triggered military restoration.

1964-1969: From the October Revolution to Ja’afar al-Nimeiry’s military coup

The key transitional issues that followed the 1964 revolution bear similarity to the 2019 uprising: conflict exacerbated by the inability to agree on a constitution that satisfies Sudan’s diversity, as well as chronic economic difficulties. However, unlike in the 2019 uprising, elections were held only a year after the military dictatorship was toppled, after an “unholy alliance” of the sectarian Umma and Unionist parties, alongside the Islamist National Islamic Front, sought early elections. Indeed, G.R Warburg declared that “the transitional period was too short”, as it did not give sufficient time to allow the fragmented coalition of political parties to form policies (Northeast African Studies, 1986).

Out of 173 parliamentary seats, the sectarian Umma and Unionist parties gained 76 and 54 respectively. Despite representing rival movements of Sufi Islamic interpretations, neither could rule without the support of the other. Meanwhile, the “ideological” parties - the Islamists and the Communists - had a limited following primarily confined to intelligentsia in urban centres, culminating in them sharing 16 parliamentary seats and unable to influence policy.

Although the “traditional” sectarian parties were the only parties able to enjoy broad support in Sudan, particularly through mobilising support networks on religious grounds, a consistent criticism of their governance has been a lack of political or economic programmes, which “creates absolute confusion”.

With no solution in sight for Sudan’s economic and security woes, Ja’afar al-Nimeiry staged a military coup in 1969, announcing “we tried liberal democracy in Sudan, it failed, and we will never go back to it”, with an analyst of the time, George W. Shepherd, writing that al-Nimeiry was “certainly correct about the failure of the political parties to deal with the basic problems of Sudan” (Africa Today, 1969).

Nonetheless, al-Nimeiry initially enjoyed the support of the Islamists and Communists, with Warburg attributing their “unholy alliance with military bedfellows” to their weak performance in the 1965 elections that indicated the unlikelihood of their ability to gain power via elections (Northeast African Studies, 1986).

1985-1989: From the April Intifada to Omar al-Bashir’s military coup

After the April 1985 civilian uprising ousted al-Nimeiry, Sudan’s political parties failed to learn from their past experiences and repeated the same mistakes that led to their 1969 overthrow, argues Kamal Osman Salih (Journal of Modern African Studies, 1990).

Again, an election was held after just a year-long transitional period, which culminated in three fragmented and unstable coalition government led by the sectarian Umma party, also featuring the Unionists, and later joined by the National Islamic Front. The first coalition government lasted less than a year. The second was brought down in August 1987 by the Unionists. Sudan was then technically without a government until May 1988, before the third and final coalition government of Umma party leader Sadig al-Mahdi’s premiership was dissolved in March 1989 after the Unionists and Islamists differed on solving the civil war. Three months later, general Omar al-Bashir would take power in an Islamist-backed military coup.

A common trend in all three democratic civilian coalitions was a paralysis of decision-making and policy development on key security and economic issues amid fierce disputes among coalition partners.

Thus, Dr. Willow Berridge, in Civil Uprisings in Modern Sudan (2015) writes: “there was a horrible feeling of ‘history repeating itself’… Sudanese politics seemed to reproduce an apparently inevitable cycle of events, whereby… a period of liberal democracy dominated by political parties relying on patrimonialism more than policy; the cynicism this experience generated then made it possible for the military to seize power once more, as it had done in 1969”.

2019-present: Will history repeat itself?

Worryingly, given the previous experiences of Sudan’s democratic transitions, Institute of Security Studies (June 3 2021) researcher Shewit Woldemichael identifies similarities between the trajectory of Sudan’s current democratic transition and its failing predecessors. In particular, Woldemichael highlights the rifts among the governing coalition of political parties and how they are impediment to policy development on key issues.

1. The key events

In September 2019, Sudan Tribune reported that a high-profile visit to Darfur by political heavyweights from the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition was met by hostile protesters who chanted “no to marginalisation” and threw stones at the politicians. The FFC delegation included Umma Party secretary-general and political veteran Sara Nugdallah, as well as Mohamed Nagy al-Assam, a leader in the Sudanese Professionals Association who is viewed as a poster boy for the uprising against al-Bashir’s regime, and Khalid Omar Yousif, the former secretary-general of the Sudanese Congress Party and currently the Minister of Cabinet Affairs in the transitional government.

Just over a year later, in November 2020, the political parties were met with public displays of hostility in Khartoum. Radio Dabanga reported that Khartoum’s Resistance Committees, grassroots neighbourhood activist networks, stormed out of talks with representatives of FFC parties on Sudan’s yet-established parliament. Clips of Resistance Committee members chanting ‘ya ahzab, kifaya azab’ (you parties, the suffering is enough) consequently circulated social media, with a spokesperson for the committees accusing the parties of “seeking to abort what is left of the revolution:”.

Recently, in a further reflection of public anger towards the civilian side of the government and the FFC parties that comprise it, Sudanese took to the streets to demand the resignation of the government following the lifting of fuel and bread subsides (AFP, 1 July 2021)

2. Why are the parties unpopular?

When the uprising was in its infancy, analytical observers had already identified a weakness in the FFC’s claimed leadership of the revolution and democratic transition – that there was no clear plan for solving Sudan’s problems after protests toppled the dictator Omar al-Bashir. As criticism of the FFC’s strategic planning continues now that they are in government, other issues highlighted include exclusionary tendencies towards non-FFC civilians, a lack of legitimacy beyond the central areas of Sudan where power historically lies, alongside a lack of popularity among the youth – a crucial demographic ahead of scheduled elections.

Less than a month after protests toppled Omar al-Bashir, Zachariah Mampilly, a Professor of Political Science at Vassar College, identified the Sudanese protest movement’s “struggle to advance a national vision beyond replacing the military with a civilian-led transition” as an obstacle to the democratic transition (Foreign Affairs, 2 May 2019). Indeed, two years later, veteran journalist Osman Mirghani, the editor-in-chief of al-Tayyar newspaper, told Radio France Internationale (23 April 2021) that “when the FFC signed their declaration, they were looking to remove the dictatorship. What will happen the day after was not considered”.

With the FFC sharing civilian government positions among its representatives, Clingendael, the Netherlands Institute of International Relations, in a lengthy report entitled “Consolidating Sudan’s transition” (February 2020), highlighted numerous issues facing the FFC parties during the transitional period, namely: the FFC’s “exclusionary tendencies” towards civilians who are not affiliated or representing its coalition of parties, the lack of legitimacy in the marginalised peripheral regions which will play a pivotal role in deciding the election, and difficulties in meeting public expectations and addressing the fundamental grievances which sparked the flames of revolution.

“Alienating” Sudanese youth

Moreover, the FFC also have trouble connecting with Sudan’s youth, who will be important in the election process, according to Dr. Azza Mustafa, a specialist on democracy and political parties, and until recently, a professor of political science at Alzaiem Alazhari University in Khartoum. Dr. Azza noted that Sudanese youth are not active in “traditional” Sudanese political parties, as they do not find “the old political programmes” attractive and are “alienated” by political parties that do not accommodate them. Thus, Dr. Azza adds, “most of the active young people join civil society organisations [rather than] political parties that still do what they did 50 years ago” (Radio Dabanga, 12 October 2020)

Indeed, upon invitation by the Sudanese Ministry of Youth and Sports, the Carter Center (August 2021), an NGO that aims to advance peace and health worldwide, surveyed 1,023 resistance committees and youth-led organisations across Sudan that formed the basis of a report on the political participation of Sudanese youth which found that:

A majority of youth are not engaged in national policymaking.

Nearly 80% of youth representatives reported that they had not been involved in any government-supported activities since the start of the transition.

Over 42% said youth had little or no voice in the transitional government, including 14% who said youth lacked any input at all.

Furthermore, in an exclusive interview with Sudan In The News, political analyst and academic at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, Dr. Ali Abdulrahim Ali, also emphasised the pragmatic importance of the parties connecting with youth. “Sudan has a median age of under 19 and 90% of the population is under 55, [making the Sudan of today] very different from the Sudan that had a freely elected parliament in 1986.” Therefore, adds Dr. Ali, “the political message to address this population must not just be revised, it must be reimagined.”

Given the view that the FFC lacks a vision and strategy to solve Sudan’s issues, alongside public legitimacy issues, it is no surprise that analysts and experts project that Sudan’s democratic transition will end in a return to military rule, in a repeat of Sudan’s previous failed democratic experiments.

3. The risk of military rule

As it stands, Sudan’s current democratic transition is following the same trajectory as the as the 1964 and 1985 uprisings, whereby “civilian governments lost popular support and were ousted in military coups within less than four years”, argues Shewit Woldemichael of the Institute for Security Studies (18 December 2020). Woldemichael adds that the FFC “needs to develop the democratic culture required to form inclusive institutions and processes.”

Indeed, the prospect of a military coup triggered by the FFC’s lack of public legitimacy was also raised by Jean-Baptiste Gallopin, a former Visiting Fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations (18 March 2020), who warned that military rule may be restored if the FFC fail to organise beyond their “narrow” social base in Sudan’s central Arab regions. Projections that the flaws of Sudan’s political parties will culminate in a return to military dictatorship at the end of the transitional period have also been advanced by influential political journalists inside Sudan.

Firstly, Osman Mirghani, the editor-in-chief of al-Tayyar, one of Sudan’s few independent media outlets, said that the democratic transition is threatened by the mistakes of civilian politicians who lack “a true vision of what needs to be done… a strategic approach and a plan” which will “enable the military to step into the gap they are creating” (Radio France Internationale, 23 April 2021).

Secondly, Asma Juma’a, the editor-in-chief of al-Democrati (17 December 2020), went a step further and warned that the political parties are the primary threat to the democratic transition. Juma’a echoed Mirghani’s point, arguing that the absence of solutions provided from the parties encourage the military to maintain state control. Furthermore, she added that while parties in countries that have entrenched democracies possess a base of supporters that they gained through their principles, vision and targeted national programmes - Sudanese parties pursue their “own narrow interests rather than offering visions and solutions.”

In summary, various analysts project that Sudan’s democratic transition will end in military rule due to the inability of the parties comprising the FFC coalition to either produce visions and solutions to solve Sudan’s issues, or articulate them and gain public support. In further exploration of the gaps of understanding between the parties and the public, Sudan In The News spoke to four people: two men and two women, of whom one of each was a representative of an FFC party and a young politically informed member of the electorate.

4. The four people we spoke to

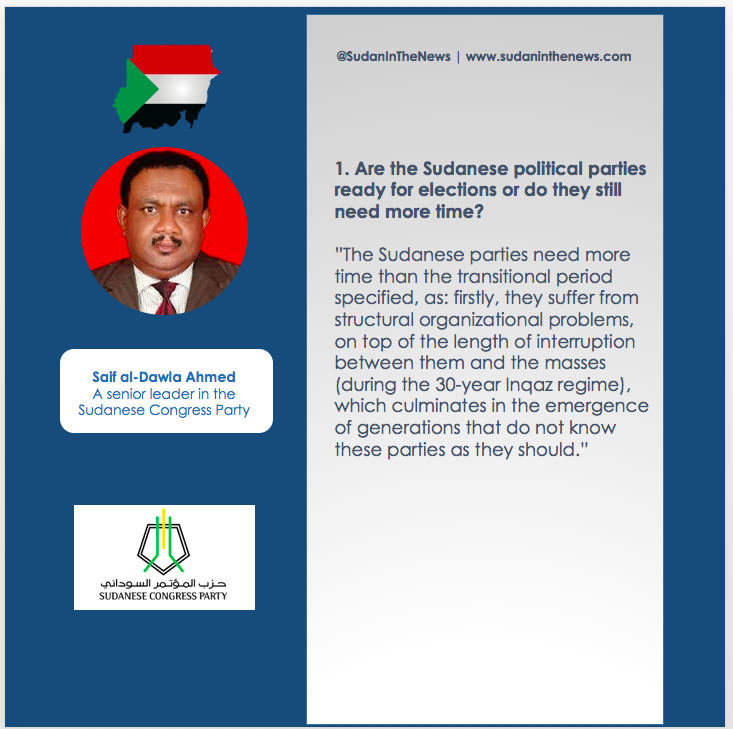

Out of the party representatives Sudan In The News spoke to, firstly, Saif al-Dawla Ahmed, a senior leader in the Sudanese Congress Party, a liberal centre-left party that was formed in 1986.

Secondly, we spoke to a woman who is a member of the New Forces Democratic Movement, also known as the Haq party – a secular party formed in the 1995 by disgruntled leaders in the Sudanese Communist Party. Unfortunately, the woman was unable to speak on-the-record due to professional commitments that do not allow political statements in public, so for the purposes of clarity, her alias in this article is ‘Rofaida’.

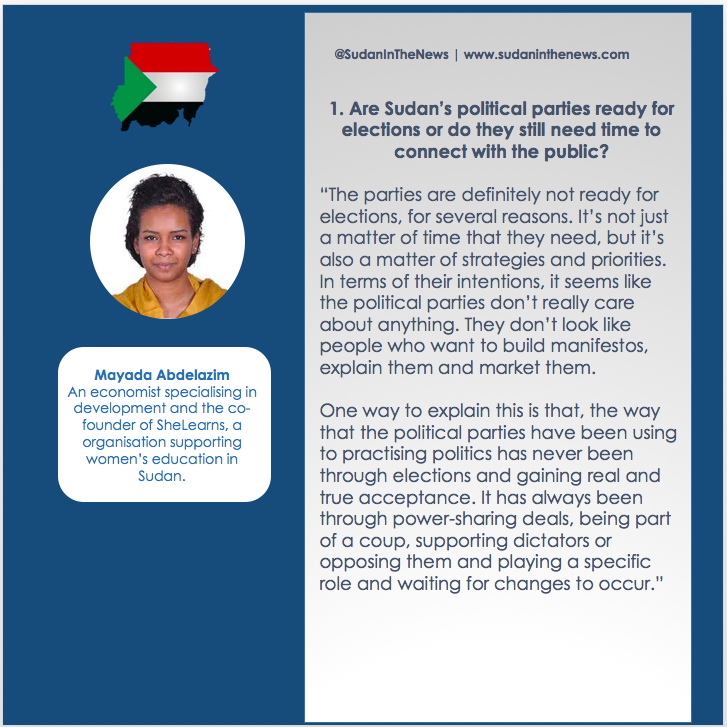

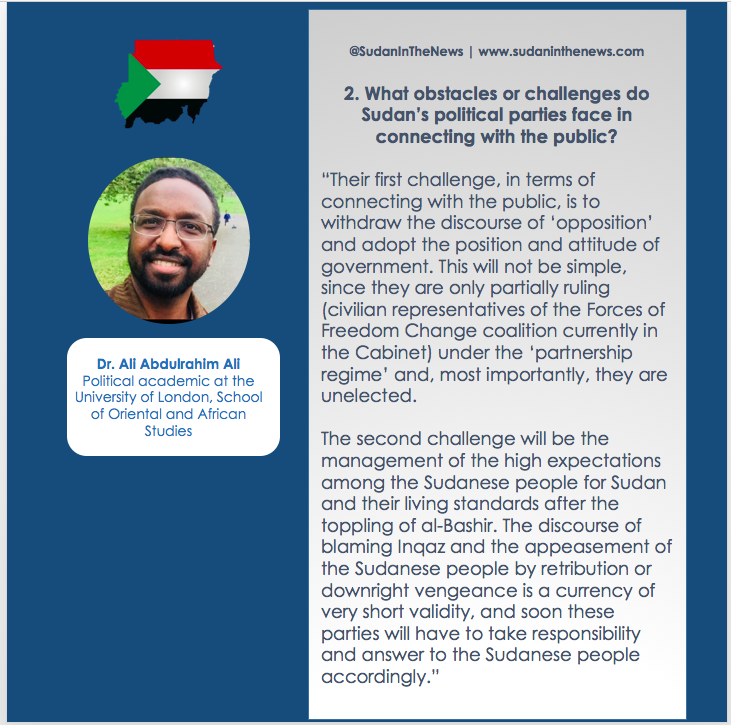

Of the politically informed citizens we spoke to, firstly, we spoke to civil society leader Mayada Abdelazim. An economist specialising in development, Mayada Abdelazim is also the co-founder of SheLearns – an organisation that supports women’s education in Sudan. Secondly, we spoke to Dr. Ali Abdulrahim Ali, a political analyst and academic at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies.

5. Are the parties ready for elections?

All four respondents agreed that Sudanese political parties are not ready for elections. Notably, the politicians gave separate reasons in comparison to the electorate.

Civilian parties lack experience in politics

Both Dr. Ali and Mayada emphasised the inexperience of Sudanese political parties in stating that they are not ready for elections, given that the thirty years of the dictatorship led by Omar al-Bashir leaves the parties with no experience of working within a democratic environment.

Dr. Ali noted that the parties “have been either working underground or accepting political ‘handouts’ of power from the regime,” with Mayada adding that “the way that the political parties have been using to practising politics has never been through elections and gaining real and true acceptance,” citing their reliance on participation through power-sharing deals, coups, supporting dictators or playing a specific role in opposing them.

In addition, Dr. Ali argues that “no experience of proper political practice can come from working under any form of tyranny, and the regime in Sudan now, while not a totalitarian state as the ousted regime, still remains a great deal under the dictates of the military junta.” He concluded that: the bottom line is, the political parties in Sudan, despite decades of experience in political struggle, are in their infancy as rulers.”

Thus, it is no surprise that the politicians we spoke to suggest that parties require an extended transitional period ahead of elections.

The parties need more time before elections, and the transitional period extended

In calling for an extended transitional period ahead of elections, Saif al-Dawla Ahmed of the Sudanese Congress Party cited factors the following factors that the parties are “suffering: from: “structural organisational problems, on top of the length of interruption between them and the masses (during the 30-year dictatorship regime), which culminates in the emergence of generations that do not know these parties as they should.”

Similarly, Rofaida of the Haq party said the transitional period must be extended, not because “[the parties] want to hold on to power, [but rather that they are] trying to build a democratic culture in Sudan” in order to avoid repeated the mistakes of previous premature elections.

Most importantly, Rofaida made the distinction between the “younger, modern” parties like her own Haq party and the Sudanese Congress Party, and the traditional sectarian conservative parties such as the Umma Party (NUP) and Democratic Unionists, who she suggests, would be the main benefactors from early elections.

Sectarian parties have a head-start ahead of the elections

According to Rofaida, the Umma Party and the Democratic Unionists, which were formed before Sudan’s independence and have experience of governing, have structural advantages ahead of elections in comparison to their younger modern counterparts, such as financial resources and networks of support, especially in the rural areas. However, Rofaida alleges the support of the sectarian traditional parties is due to clan networks and strategic alliances with tribal leaders, which is “what we [the modern parties] are trying to change”.

Expanding on the prospect of the traditional parties performing better in the elections, and what it means for Sudan’s democratic culture, she said: “we want Sudanese politics to be a battle of ideas and visions. Not ‘I will vote for this person because this person told everyone in my family to do so’. If the election is decided on the grounds of mobilising sectarian and clan networks then the outcome would be that Sudanese politics will still be decided on the basis of exchanging favours, rather than ideas. This is not a productive environment to consolidate democracy and solve Sudan’s issues.”

Nonetheless, Ali argues that while the traditional parties may win seats in any future parliament and form a coalition government, “[they] are now lead by second or third generation politicians with very limited experience in parliamentary politics or even preparing for elections.”

Perceptions that the parties do not have strategies

The lack of readiness for elections among Sudan’s political parties is also a matter of strategies and priorities, according to Mayada. She said that “in terms of their intentions, it seems like the political parties do not really care about anything. They don’t look like people who want to build manifestos, explain them and market them.”

6. What challenges do the parties face in terms of connecting with the public?

All four respondents said that communication was the key barrier preventing the parties from connecting with the public. 3 of the 4 respondents highlighted logistical issues such as: the absence of independent media and communication expertise. Dr. Ali, however, identified the FFC’s discursive practices as a hindrance to their ability to closely connect with the public .

Communication

3 out of 4 respondents identified communication as a logistical barrier prevent the parties from connecting with the public. On top of noting the pre-existing hindrance to the parties public engagement capabilities caused by 30 years of dictatorship, Saif al-Dawla Ahmed also cited the financial inability of the parties and the “absence of a practicing and trained cadre on communication and mass communication processes.”

The Haq Party’s Rofaida also identified these obstacles, stating that the parties “lack resources and expertise in communicating with the masses”. However, Rofaida highlighted specific aspects that entrench the communication gap between the parties and the public, stating that: “many of the parties are reliant on old-fashioned methods of communicating such as rallies and public meetings, but the new generation are not interested in this.” Furthermore, she adds that the matter is compounded by anti-democratic forces that were affiliated to the ousted regime possessing “the most advanced mastering of social media and mass communications practices”.

In addition, Mayada also suggests that communication is one of the most important barriers between the public and the parties, particularly the absence of independent media. She states that during al-Bashir’s regime “there was no media outlet that was trustworthy and reliable that was reporting from the ground. There were no unbiased media channels. All the big ones that people would follow were monitored by the government.” Mayada added that “the political parties had to opt for alternative methods, primarily social media, which became linked to fake news and rumours”.

FFC Discourse: “a currency of very short validity”

Meanwhile, Dr. Ali identified two challenges facing the FFC’s ability to connect with the public, with both falling into the category of the coalition’s discursive practices. “Their first challenge is to withdraw the discourse of ‘opposition’ and adopt the position and attitude of government.” Dr. Ali adds that the second challenge for the FFC is to manage the expectations of Sudanese people with regards to standards of living, with “the discourse of blaming the former regime [being a] currency of very short validity, and soon these parties will have to take responsibility and answer to the Sudanese people accordingly.”

7. Do the parties have visions and solutions for Sudan’s problems?

Then, we asked our politicians to respond to the accusations that parties lack a vision and strategy for solving Sudanese issues, alongside asking the citizens if they feel that the parties have a vision and strategy. Saif al-Dawla Ahmed of the Sudanese Congress Party agrees that the parties were unable or interested in developing political strategies, although he differentiates between the traditional and modern parties as to why. However, Rofaida says that her party does have visions and solutions for Sudan’s issues, but attributes accusations the accusations to the lack of a platform that allows the parties to articulate their visions before the masses.

Meanwhile, Dr. Ali and Mayada highlight specific obstacles preventing the parties from developing visions and strategies: namely, how Sudan’s brain drain limits the depth of political participation from those capable of providing the necessary “new and inventive” visions to solve the “chronic economic situation, alongside the parties’ focus on short-term priorities such as survival.

“Sectarian parties are not interested in strategies”

Saif al-Dawla argues that the traditional sectarian parties, the Umma Party and Democratic Unionists, are not interested in strategies “as they are electoral parties that depend on their masses, so the course of their competition is to create the largest amount of sectarian, tribal and clan bases and networks, as opposed to building support on the basis of strategies and programs.” Similarly, Mayada notes that many do not trust the sectarian parties, who despite possessing the “biggest base of supporters”, have a predominantly religious following that trusts their leaders as “icons and religious symbols” rather than political figures.

Short-term priorities like survival take precedence over the production of long-term visions and solutions

Nonetheless, Saif al-Dawla attributes the absence of strategy from “modern parties such as the Communist Party, the Sudanese Congress Party and the Baath Party [who] try to base their political competitiveness on the basis of programmes and strategies” to the lack of continued democracy and totalitarian rule.

To supplement Saif al-Dawla’s argument, Mayada provided more granular analysis, telling us that: “in the last 30 years, most parties were in survival mode and did not have enough space to develop well-thought out strategy. Everyone was too busy trying to not get caught, or free their friends who were caught”.

Even now that the FFC are in government, short-term survival continues to take precedence over the long-term development of strategy, notes Ali, who attributes the parties inability to develop strategies and visions to most parties “thinking their chances of political success in a free and fair elections are small,” leaving their priority to “prolong the transitional period, perhaps indefinitely, if they can conspire with the military junta.” Ali adds that this “falls in direct opposition to the Sudanese goal of transforming Sudan into a democracy.”

The lack of platforms to present visions and strategies

However, Rofaida claims that her party, Haq, does have strategies and visions to solve Sudan’s issues, but asks “where can we present it?”. Rofaida states that much of the media in Sudan is subject to the control or influence of the former regime, and that attendants of party rallies tend to be people who already support a party rather than interested observers who need to be won over. Thus, she claims, “the issue for Sudan’s political parties is that many in the public do not know what we stand for.”

Brain drain: talented Sudanese have “little incentive to be part of the political mess”

Dr. Ali identifies Sudan’s brain drain, whereby Sudanese professionals leave the country for economic or social reasons, contributes to situation that culminates in citizens of high potential to contribute to solving Sudan’s issues, are not doing so. While Sudan’s “chronic economic situation makes a new and inventive vision necessary,” Ali notes that “the talents that can bring about the right visions and ideas are not part of the political parties now. They are mostly a diaspora with little incentive to be part of the political mess in Sudan.”

8. Is there distrust between the public and the parties?

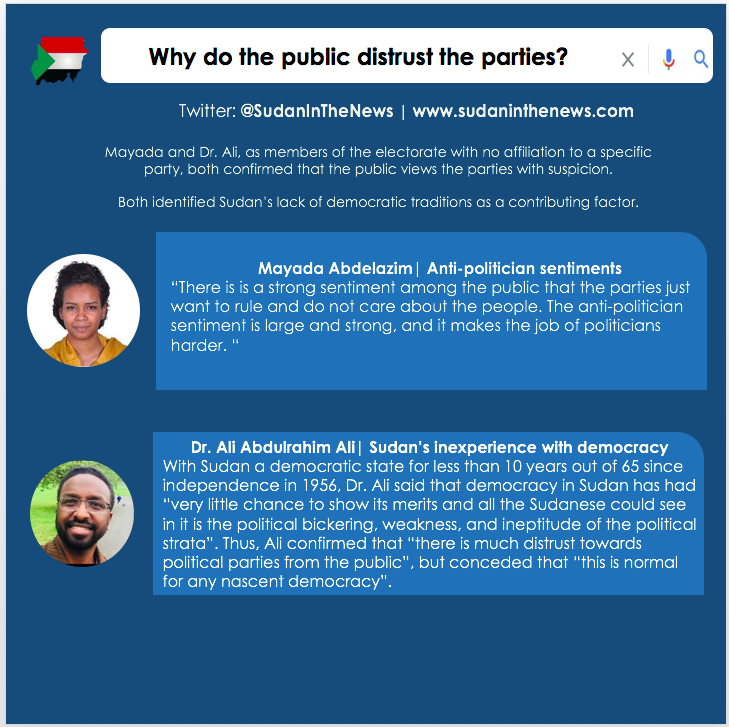

Dr. Ali and Mayada, as citizens with no affiliation to any political party, both confirmed that public views the political parties with suspicion. Both identified Sudan’s lack of democratic tradition as a contributing factor. In part 9, all four respondents explain why youth are not participating politically through the FFC parties, and the importance of the youth ahead of the elections.

Inexperience with democracy

Dr. Ali states that Sudan’s minimal experience with democracy – with Sudan a democratic state state for less than ten years of 65 since independence – means that “there is much distrust towards the political parties from the public.” Dr. Ali adds that democracy in Sudan has “had very little chance to show its merits and all the Sudanese could see in it is the political bickering, weakness, and ineptitude of the political strata,” although he further notes that “this is normal for any nascent democracy”.

Similarly, Mayada told us, “if we are using the approach of comparing Sudanese political practice to the politics practised in mature western liberal democracies, then we are failing. The way the Sudanese state was built does not accommodate liberal democratic political practice, and the evidence of this lies in our experience of coups and civil wars.”

Anti-politician sentiments

Also confirming the public hostility towards the political parties, Mayada said: “there is is a strong sentiment among the public that the parties just want to rule and do not care about the people. The anti-politician sentiment is large and strong. I’m not sure of its origins, but it definitely exists and it makes the job of politicians harder.“

9. Parties relationship with youth

With Sudan’s young population making the youth a crucial demographic target in any pursuit of electoral success, a disconnect between the youth and the parties has been acknowledged. However, while the Sudanese Congress Party’s Saif al-Dawla identifies the former regime as a contributing factor to this disconnect, Mayada notes that many youth felt betrayed by the parties after the horrific incidents of the June 3 massacre. Interestingly, Rofaida says that the parties are competing with the Resistance Committees for the contributions and support of politically active young people.

Youth do not know the parties

Saif al-Dawla says it is “natural” that the youth do not trust the parties, as “they do not know them and they have been influenced by the media of the previous regime, which has demonised the parties for a period of three decades.”

Youth feel betrayed

However, Mayada, herself a young Sudanese civilian who the parties aim to win over, says the youth do not feel connected to the parties because “a lot of youth lost hope in the parties and felt like they were betrayed,” in the aftermath of the FFC entering a power-sharing government with the military after the June 3 massacre.

Political parties must compete with resistance committees and civil society organisations for youth participation

According to Rofaida, a consequence of the youth’s distrust of the parties is that they are competing with the Resistance Committees for young talent and support. She told us: “many of the visionary Sudanese youth, who have ideas, leadership qualities and the charisma to engage well with the wider public, opt to remain independent of any parties and instead chose to serve or support the Resistance Committees.”

As well as emphasising the need to integrate such youth into the parties, she also said the parties “could do better to engage with the youth on their preferred methods of communication, like social media.”

It is worth noting that, as mentioned earlier in the report, Dr. Azza Mustafa, a specialist on democracy and political parties, and until recently, a professor of political science at Alzaiem Alazhari University in Khartoum, pointed out that “most of the [politically] active young people join civil society organisations [rather than] political parties that still do what they did 50 years ago.”

Youth are important in the election

Ahead of the elections, there is also strategic importance for the parties in establishing close relationships and gaining the support of Sudanese youth. According to Dr. Ali, Sudan – “with a median age of under 19 and 90% under 55 is very different from the Sudan that last had a freely elected parliament in 1986.” Thus, Dr. Ali suggests that “the political message to address this [young] population must not just be revised, it must be reimagined.”

10. Women’s representation

Finally, the parties have also been accused of excluding women. Mayada blames the wider patriarchal nature of Sudanese politics, while Rofaida alleges a reluctance to adopt radical policies for women’s empowerment.

“Political practice in Sudan excludes women”

“Women’s representation in Sudanese politics is generally not good” as “Sudanese political institutions are very patriarchal, sexist and not very inviting to women”, explains Mayada, who further notes that “political practice in Sudan is also done in a way that excludes women”. She provided example of political meetings being held late into the evening, “even though many women in Sudan cannot just be outside in public places during these hours of the night.” In addition, Rofaida notes that: “condescending attitudes towards women in politics still prevail. There is this belief that politics is “men’s talk”.

Reluctance to empower women

However, Rofaida also argues that the inclusion of women is more than “just a matter of representation,” citing how the ousted regime had quotas for women’s representation in parliament despite overseeing repression and infringements of women’s liberty. In particular, she points to a “reluctance” among parties to adopt radical visions and solutions for women’s empowerment that are being proposed by women’s rights groups.

Sudan In The News is a youth-led organisation currently developing a project to enhance Sudan’s democratic culture and enhance the political participation of Sudanese youth. For further information on our project and potential partnership opportunities, please contact sudaninthenews@gmail.com