Will the framework agreement in Sudan lead to democracy?

Introduction

1. On 5 December 2022, a framework agreement was signed between the Sudanese military and civilian political parties. The deal aims to end the political crisis triggered by the 25 October 2021 military coup by paving the way for a two-year civilian-led transition towards elections.

2. However, the agreement is rejected across Sudan’s political spectrum from both anti-coup and pro-coup forces.

3. Section three synthesises analysis that has highlighted the positive potential of the framework agreement (3.1), followed by the negatives (3.2).

4. Section four explores the public distrust towards the military and civilian signatories of the framework agreement. The military’s commitment towards democracy has been questioned (4.1). On the other hand, various analysts deem the civilian signatories of the framework agreement inept at leading Sudan’s path towards democratic governance (4.2).

5. Finally, section five summarises proposed solutions for the framework agreement to be implemented effectively and deliver democratic governance. Solutions have been directed towards the civilian signatories of the agreement (5.1), and the international community (5.2).

1. Developments

The first section gives a brief overview of the framework agreement and what it promises.

1.1 What is the framework agreement?

Following weeks of US-brokered negotiations that saw the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia hold direct talks with the political parties belonging to the Forces of Freedom and Change Central Council (FFC-CC), the framework agreement was signed by the aforementioned parties (Bloomberg, 5 December).

1.2 What does the framework agreement entail?

According to the signatories, the deal provides would pave the way for two-year civilian-led transition towards elections, which would start with the appointment of a prime minister chosen by the FFC-CC (Sudan Tribune, 5 December). Aspects of the deal include:

The military agreeing it would only be represented on a security and defence council headed by a prime minister (Reuters, 5 December).

The establishment of a single professional army, with the RSF integrated into it and an Interior Minister controlling all security forces.

The military would only be allowed to conduct commercial business in its industry.

The commander-in-chief of the army would be the civilian head of state, who also picks the head of the General Intelligence Service (Sudan Tribune, 5 December).

1.3 What are the next steps of the framework agreement?

Phase 1 of the negotiations that aim to implement the framework agreement cover five key policy areas: transitional justice, security sector reform, dismantling the remnants of the ex-president Omar al-Bashir regime, the Juba Peace Agreement and the crisis in eastern Sudan (Radio Dabanga, 4 January).

Mohamed Abdelhakam, a leading member of Sudan’s Federal Association and the FFC-CC, said he believes that the prime minister should be chosen from a pool of technocrats who are not involved in partisan work. He also stressed the necessity of forming “a government of independent voices without partisan quotas, provided that the parties devote themselves to preparing for the elections” (Radio Dabanga, 15 March).

Khalid Omar Yousif, the spokesperson for the signatories to the framework agreement, said there was an agreement to form a new transitional government on 11 April 2023, with a constitutional declaration to be signed on 6 April 2023 (Multiple sources, 19 March).

However, the deal faces various obstacles, starting with its rejection by political groups that both rejected and supported the 25 October 2021 military coup.

2. Who has rejected the framework agreement?

The framework agreement has been rejected across Sudan’s political spectrum – with both anti-coup and pro-coup groups opposing the deal.

2.1 Resistance committees

Despite some acceptance by resistance committees in Sudan’s marginalised peripheries, the framework agreement has been mostly rejected by Sudanese resistance committees – particularly those in Khartoum state.

In reaction to the signing of the framework agreement, the Resistance Committees - “the largest of the popular gatherings opposed to military rule” (Fanack, 10 January) - announced protests in line with the slogan they adopted in response to the political crisis the followed the 25 October 2021 military coup: “no negotiation, no partnership, no legitimacy” (Radio Dabanga, 5 December). As a result, the deal is yet to gain buy-in from the resistance committees who “formed the core of the protests against ex-president Omar al-Bashir’s regime but have since sparred with the FFC” (International Crisis Group, 23 January).

Two days before the signing ceremony of the framework agreement, the coordination of Khartoum Resistance Committees (3 December) published a statement entitled ‘Let the traitors fall’ which stated that: “Transforming the project of the great Sudanese revolution into a project for a political settlement” that recognizes the coup regime is not only a matter of “high treason” but also breaks from the revolution.

However, the resistance committees are not a monolith and there have been contrasting perceptions according to geographic location.

Reporting on the mixed reactions by different resistance committees, Radio Dabanga (7 December) quoted resistance committee members in al-Jazira state and Kassala who rejected the framework agreement. However, Ismail Kenek from the resistance committees of the Blue Nile region was quoted to welcome the signing of the framework agreement, saying that “it fulfils the demands for a radical solution gradually and works to solve crises, especially for the Blue Nile Nuba Mountains region.” Similarly, his colleague Osman Ghaboush agreed said: it is “an acceptable solution that presents a roadmap to get out of the current stalemate,” before calling for “credibility in its implementation.”

2.2 Left-wing political parties

The Communist Party of Sudan and the mainstream Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party vehemently reject the framework agreement and have rallied public opposition towards it.

Calling on its members to join the marches organised by the resistance committees against the agreement, the Communists labelled it “a domestic and foreign conspiracy to block the path of the revolution” (Radio Dabanga, 5 December).

Like the coordination of Khartoum resistance committees, the Alliance of Forces for Radical Change (AFRC), a coalition led by the Communist Party, also published a statement two days before the framework agreement was signed which labelled it a “legitimisation of the authority of the 25 October 2021 coup”. The Communist-led AFRC further stated that “the interests of politicians seeking to inherit the former regime are integrated with the ambition of the military to continue their political and economic control, and justice for the martyrs is a ‘minimal’ price for the continuation of this alliance” (3 December).

The mainstream Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party later announced its departure from the FFC coalition, stating that the agreement is “devoted to legitimising the October 25 coup” as both the Communist Party and Resistance Committees suggested (Radio Dabanga, 15 December). Nonetheless, the agreement is also rejected by pro-coup forces.

2.3 Islamists

Islamist groups reappeared on Sudan’s political scene after the 25 October 2021 coup, with the army’s commander-in-chief Abdulfattah al-Burhan seeking to use them to gain civilian backing for his coup. Yet, despite holding a dialogue in favour of the coup leaders shortly before the framework agreement was signed, People’s Call, an Islamist coalition, demonstrated in Khartoum in opposition to the deal. Mohamed Ali al-Jizouli, the leader of a radical Islamist group, warned: “we will resist the leadership of the military component and are ready to close the East and North and transfer the protests to the Army General Command” which Sudan Tribune (3 December) stated meant “they would call on the army to side with them and seize power.”

2.4 FFC-DB

The framework agreement is rejected by a pro-coup faction of the Forces of Freedom and Change entitled the Democratic Bloc (FFC-DB) (Sudan Tribune, 2 December).

The FFC-DB coalition comprises of factions of armed movements that fought al-Bashir’s regime before allying with the military, alongside pro-military factions of Sudan’s two largest traditional sectarian parties (Sudan Tribune, 3 November). They include:

The Sudan Liberation Movement faction of governor of Darfur Minni Minnawi (SLM-MM)

The Islamist Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) led by finance minister Jibril Ibrahim.

Mubrak Ardol, the head of Sudan’s Mineral Resources Company and a former Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) official.

Ja’afar Mirghani, who leads a pro-coup faction of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

Mubarak al-Fadil, the head of a pro-coup faction of the National Umma Party (NUP) (Sudan Tribune, 30 December).

With the armed movements – JEM and the SLM-MM – commanding “widespread support” across Sudan’s peripheries, Fanack (10 January) suggest that “the combined weight of [FFC-DB] affords them the ability to obstruct the implementation of the framework agreement especially since their positions align with [Egypt]...which has a considerable impact on the political balances in Sudan.

The International Crisis Group (23 January) attribute JEM and the SLM-MM’s rejection of the agreement to their signing of the Juba Peace Agreement (JPA) which promised its signatories 25% of seats in the civilian administration alongside other important concessions. Thus, the rebel movements will “resist any attempt to dilute their hard-won gains” due to their objection to language in the framework agreement which suggests that the JPA may be renegotiated.

For more information on the FFC-DB and their position on the framework agreement, please read our analytical briefing: Is Egypt playing divide-and-rule in Sudan?

3. Analysis

The first analysis section of the framework agreement reports starts by synthesising analysis that has highlighted sources of optimism and positivity around the framework agreement (3.1). However, this will be immediately followed by negatives about the agreement itself (3.2).

3.1 Positives

3.1.1 Resolving the economic crisis

If successfully implemented and civilian-led government returns, the deal could: restore billions of dollars of Western financial help, speed large-scale investment from Gulf Arab nations including in ports and agriculture, alongside reviving plans for Sudan to receive debt relief under an International Monetary Fund initiative (Bloomberg, 5 December).

3.1.2 Resolving security crisis

Amid protests in Khartoum against the framework agreement, Radio Dabanga (5 December) report on positive perceptions in the peripheries. The Darfuri Civil Society Platform signed the framework agreement, describing it as “a new and excellent opportunity to address and discuss Sudanese problems that have existed for decades, pave the way for future generations, and end the sharp polarisation.” In addition, Awatef Abdelrahman, head of the Sudanese Displaced Women Network, called on “all forces to sign the framework agreement in order to implement the Juba Peace Agreement, which will allow the displaced to return home.”

3.1.3 Optimism about the FFC’s leadership

Marina Ottaway, a Middle East Fellow at the Wilson Center (5 January), identified two sources of “guarded optimism” that a democratic process can emerge from Sudan’s Framework Agreement. Ottaway argues that the FFC is better equipped to lead Sudan’s democratic transition in comparison to other civilian forces that have been historically powerful.

Ottaway noted how Sudan’s previous three experiences with civilian rule (1956-58, 1964-68, 1985-89) saw the government controlled by coalitions in which power was shared by the traditional sectarian parties – the NUP and DUP – that were deemed incapable of cooperating or governing effectively. However, she noted that the traditional parties “are no longer controlled by dynasties, and their importance has faded compared to that of newer organisations”. Ottaway further noted the decline of the Islamic Movement.

However, Ottaway adds, the “Forces of Freedom and Change represent a broader section of the population; they are younger, more mobilized and better led”.

3.1.4 Compromise from the military

The second source of optimism highlighted by Ottaway is that “most of the military leadership seems to realise that they cannot rule alone,” which is conducive towards compromise.

3. 2. Negatives

3. 2.1 Lack of details

The framework agreement has been criticised on the grounds that it does not set out a specific path for the reforms it promises. Firstly, the outline pact of the framework agreement has set no date for a final agreement or the appointment of the prime minister who is meant to lead a two-year transition towards elections (Reuters, 5 December). Secondly, although the deal envisions Sudan’s military stepping back from politics by forming part of a new ”security and defense council” under the appointed prime minister, “it does not address how to reform the armed forces, saying only they should be unified and controls should be imposed on military-owned companies” (AP, 5 December).

3. 2. 2. Unrealistic time frame

The framework agreement has also been criticised for setting unrealistic deadlines for complex reforms. Kholood Khair, founding director of Confluence Advisory think-tank, said: “realistically none of these complex processes can be dealt with within a transitional time frame of two years” (AP, 5 December). Similarly, human rights lawyer Najlaa Ahmed identified an “ambitious list of reforms that is unrealistic for a two-year transition,” citing the lack of time frame for a final agreement that is meant to contain detailed provisions on the military, security sector, judiciary and law reform (Rights for Peace, 26 February). Ahmed also raised concerns about the number of issues “deferred” for further discussion, which has also been a common theme of criticism.

3. 2. 3. Defers important issues

With AP (5 December) noting that the deal “appears to leave many thorny issues unresolved,” Reuters (5 December) add that it has left sensitive issues including transitional justice and security sector reform for further talks. As a result, Cameron Hudson of the Center for Strategic and International Studies said: “it is massive embarrassment for the international community… which celebrated Sudan’s civilian transition three years ago…[who] believe that any deficiencies in this agreement can be made up for in subsequent rounds of negotiations” (Voice of America, 6 December). Among the crucial issues deferred for further discussion is transitional justice.

3.2.4 Transitional justice

Rights for Peace (26 February) questioned how the framework agreement would build on previous agreements regarding transitional justice, accountability and reparation for those who suffered gross human rights violations such as torture, conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) and mass atrocity crimes. This includes the implementation of a law establishing the Transitional Justice Commission that was adopted by former prime minister Abdallah Hamdok’s government in June 2021.The organisation also raised concerns that CRSV is not mentioned at all in the agreement.

4. Why are the framework agreement signatories distrusted?

A key hindrance towards the implementation of the framework agreement is public distrust towards both its military and civilian signatories. Rift Valley Institute fellow Magdi al-Gizouli noted that the signatories “have quite limited public trust in them” (Reuters, 15 December), while Kholood Khair said the deal “does not inspire confidence that it will lead to the reforms that people want to see,” and it is “contingent on public trust in the protagonists [which] does not exist” (AFP, 6 December). As a result, part four will focus on why there is a lack of trust in the military and civilians. Whereas analysts predominantly question the democratic commitment of the military, they also criticise the political aptitude of civilian political parties given their exclusionary tendencies and ineffective policymaking.

4.1 The Sudanese military’s questionable democratic commitment

4.1.1 Can the military be trusted?

With observers questioning whether the military would be willing to give up economic interests and wider powers that it views as its privileged domain (AFP, 5 December), recent military actions and statements have raised doubts about the military’s commitment to the democratic reforms promised in the framework agreement.

Firstly, there is the issue of civilian-led security sector reform – a major demand of Sudan’s pro-democracy movement. Yet, in a speech shortly after the agreement was signed, the commander-in-chief of the Sudanese army, Abdulfattah al-Burhan, told his troops: “do not listen to what politicians say about military reform. Nobody will interfere in the affairs of the army at all” (Sudan Tribune, 14 December).

Secondly, there is the issue of which civilian entities can participate in the political process following the framework agreement. The FFC-CC seeks to exclude “non-revolutionary and pro-coup forces” who they say would “flood the process of democratic transition” (Sudan Tribune, 5 January). This includes parties that it says are not interested in democracy, such as the FFC-DB - which backed the 2021 military coup (Multiple sources, 5 February).

Yet, al-Burhan called for an expansion of signatories to the Framework Agreement, which leading FFC-CC member al-Muez Hadrat alleged was a tacit call for the return of the National Congress Party (NCP) – the Islamist ruling party of al-Bashir’s regime (Sudan Tribune, 5 January). Then, al-Burhan’s army and ruling Sovereign Council colleague, Lt Gen Shamseldin Kabbashi, claimed that the Sudanese army will not protect a [framework agreement] signed by 10 men,” in comments labelled by Siddig Tawir, a civilian member of the pre-coup Sovereign Council, as “an expression of his anti-democratic behaviour” (Multiple sources, 5 February).

The military’s actions before and after the framework agreement have also raised doubts about their commitment to the framework agreement. Kholood Khair, the founding director of Confluence Advisory think-tank, noted that the framework agreement hinges upon the word of military actors “who staged a violent coup in 2021” and have not curbed violence against protestors since the agreement was signed (Arab Center DC, 23 January).

As such, doubts about the military’s intentions and democratic commitment has informed analysis that its signing of the framework agreement is merely a strategic retreat.

4.1.2 The deal is considered a strategic retreat for the military

Given the internal and external pressures facing the military following a worsening economic crisis triggered by the 2021 coup, various analysts suggest that the framework agreement offers the military a lifeline that can pave the way for further power grabs.

With Kholood Khair suggesting that phase one of the deal "is a very low level commitment on al-Burhan's part... allowing him to survive" politically (AFP, 5 December), Cameron Hudson said he is skeptical that Sudan’s framework agreement “is anything more than a tactical maneuver by the military to buy more time and space” as it “essentially returns Sudan to the position it was in originally in 2019 after the fall of al-Bashir” (Al-Monitor, 5 December).

The military’s withdrawal from power can be attributed to its inability to institutionalise and consolidate its rule following the 2021 military coup, argues Hager Ali, a doctoral researcher at the German Institute for Global Area Studies. As the dissolution of the NCP left al-Burhan “without any prefabricated structures for effective governance”, Ali argued that “Sudan’s economic crisis requires a much faster consolidation of government to avert state collapse,” as the loss of foreign aid in response to the coup triggered worsening crises that aggravated citizen backlash and can turn army factions against al-Burhan. However, Ali identifies “high conflict risks” if “al-Burhan’s institutionally weaker new regime” tries to generate state revenues to fund direct military rule by exploiting important natural resources located in Sudan’s peripheries, as doing so would “fuel the same grievances that mobilised the Sudanese people against al-Bashir” (Political Violence At A Glance, 10 January).

Nonetheless, the framework agreement will likely maintain the military’s upper hand over pro-democracy civilians, notes Hudson (Voice of America, 6 December). With the agreement keeping military leaders in their roles, Rift Valley Institute fellow Magdi al-Gizouli said the door is open for military intervention in civilian affairs and “a door closed to civilian intervention in military affairs” (Reuters, 15 December).

Furthermore, Council for Foreign Relations (11 January) warn that extended “transitional” periods – as promised in the framework agreement - that empower the military and “give them ample opportunities to engineer the kind of instability that they can later argue requires their continued control”.

Alternatively, at the end of the transitional period, the military may consolidate and institutionalise their control via elections, with Hudson questioning whether any future elections in Sudan, if they occur, will be free and fair or “lead to the fundamental transformation of the Sudanese state” adding that “the leopard has not changed its spots and there is nothing in evidence to suggest that it intends to going forward” (Al-Monitor, 5 December).

4.1.3 Elections to consolidate military rule

Although Sudan’s weak electoral infrastructure has the double-edged risk of both empowering the military before elections, and facilitated legitimised autocratic military rule via the ballot box.

With credible elections requiring broadly accepted parameters that ensure that losers respect the legitimacy of elected institutions and winners do not “push victory to extremes [and act with] no limits in power”, Sami Abdelhalim Saeed, the head of the Sudan programme at the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, wrote that the lack of scope of elected institutions under Sudan’s 2019 Constitutional Charter are “an invitation to instability”. Saeed argued that the requirement that elections in Sudan happen at the end of a transition “place a huge burden” on the country’s unelected transitional institutions to develop a permanent constitution. Thus, Saeed raised the prospect of either: a rushed constitution that compromises on quality and checks and balances on electoral winners, or delayed elections that increase the risk of extra-constitutional military intervention (Atlantic Council, 30 January).

Nonetheless, there is also the argument that the military is using the framework agreement as a tool to consolidate is power electorally. When the framework agreement was still under negotiation, analyst Jihad Mashamoun wrote an article for Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (15 November) which suggested that, with elections planned for 2024, al-Burhan was serving his presidential ambitions by “strategically” using dialogue with the FFC.

Mashmoun suggested that al-Burhan fears that factions of al-Bashir’s regime may launch a coup against him. Ibrahim Ghandour, Ali Karti and Amin Hassan Omar were identified as al-Burhan’s presidential rivals, with the former regime stated to have 500,000 supporters who control the economy and state institutions, supplying them with considerable funds and organising power to win or rig elections “as they have done in the past”. In addition, Mashamoun highlighted competition al-Burhan faced from within his own coalition: finance minister and JEM leader Jibril Ibrahim was “working to unite the former regime and [Islamist] Popular Congress Party” and Rapid Support Forces commander Himedti was “shoring up support in Darfur through the reconciliation of Arab and African tribes.”

4.2 The weakness of Sudan’s civilians

While the framework agreement offers the military a strategic retreat, it "works out less well for the civilians who will have to do the hard work and sell it to the public,” notes Kholood Khair (AFP, 6 December). This section explores criticisms and challenges confronting the civilian component of the framework agreement. An obstacle to the implementation to the agreement are Sudan’s “weak” civilian political parties, with those who dominate the FFC-CC deemed inept at leading Sudan’s path towards democratic governance.

4.2.1 Weak political parties

Hala Al-Karib, the Regional Director of SIHA (the Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa), identified obstacles preventing Sudan’s pro-democracy movement from transforming into an effective vehicle for democratic governance. Al-Karib wrote that the women and youth who were “truly responsible” for toppling Omar al-Bashir’s regime “had to yield to the leadership of weak and isolated political parties”. Al-Karib added that Sudanese political parties’ attempts to lead the political transition after the revolution “were doomed to failure” as they had long lost any connection they had with the people, were solely interested in self-preservation and “failed to engage with and accommodate in their policy plans the new waves of activism led by women, youths and minorities” (Sudan Tribune, 12 January).

4.2.2 The exclusion of influential civic groups

The failure to include, and forge consensus with, influential civic groups in the process leading up to the framework agreement is argued to increase the risk of another military coup, particularly as both the negotiations that preceded and succeeded the framework agreement have been deemed exclusionary.

The International Crisis Group (ICG, 23 January) suggest that the “biggest and most legitimate concerns” regard the process. ICG cited the FFC-CC’s direct negotiation with the military rather than forging consensus with the resistance committees. ICG also alleged the FFC-CC alienated “other important actors” including ex-rebel leaders and tribal groups with constituencies far away from Khartoum, as well as Islamists who lost power when al-Bashir fell.

As a result, ICG (31 January) note – the deal is yet to gain buy-in from the aforementioned groups – particularly the resistance committees who “formed the core of the protests against al-Bashir’s regime but have since sparred with the FFC”. Thus, ICG warn that unless the FFC leaders make genuine efforts to forge a broader coalition with civilian groups that are critical of the framework agreement, their exclusion will affect the credibility of any final agreement and the legitimacy of the civilian government that will take power. Without broader support, Sudan’s next government risks falling again, possibly to another coup, ICG add.

Thus, the framework agreement “re-entrenches Sudan’s cardinal weakness” - that political settlements only create winners and losers and thus do not result in a government for all, but rather, in a minority government of elite interests,” with Kholood Khair drawing attention to “opaque and exclusive methods” under which post-agreement negotiations have commenced (Arab Center DC, 23 January). It is no surprise then that the negotiations that have followed the framework agreement have been deemed “elitist” and Khartoum-centric.

4.2.3 Khartoum-centric

Radio Dabanga (9 January) reported that Darfur’s displaced have labelled “elitist” the series of workshops held by the signatories of Sudan’s framework agreement. Lawyer al-Moez Hazrat said that conferences on transitional justice held in “air-conditioned ivory towers” will not be able to achieve justice. He called for holding one of the planned workshops on transitional justice in a camp for the displaced in Darfur emphasising how holding grassroots conferences with the participation of stakeholders is “especially important [as] we would benefit from the views of native administration leaders in this transitional justice process.”

Similarly, Sheikh Abdelrazeq, a leader of Darfur’s displaced, said the “elitist” workshops will not achieve justice as “they are confined to Khartoum without any coordination with the victims.” He called on the signatories to reach out to people in Darfur.

Therefore, the exclusionary nature of the negotiations that preceded and followed the framework agreement, alongside the pre-existing representation and policymaking weaknesses of Sudan’s political parties, combine to culminate in weak civilian institutions that may struggle to tackle the complex policy challenges that the framework agreement intends to solve.

4.2.4 Can civilians implement the framework agreement?

Amid the pre-existing criticisms of the exclusionary tendencies of Sudan’s political parties, political analyst Bakri al-Jak warned that the agreement may bring about “a lame government” instead of political stability (Radio Dabanga, 4 January). With the agreement aiming to tackle issues that fuelled civilian-military tensions before the October 2021 coup - reform of the security forces, justice for civilians killed during protests, dismantling al-Bashir’s regime and resolving internal conflicts

Khaled al-Tijani, editor of Elaph newspaper, said the aforementioned policy areas “could be the future cause of the agreement's collapse” (Reuters, 15 December). Similarly, Kholood Khair said the signatories will likely face "a real political crisis as they start talking in earnest about security sector reforms, transitional justice (and) financial accountability” (AFP, 5 December).

Political analysts have particularly questioned the capacity of the framework agreement, and its signatories, to resolve Sudan’s internal conflicts. Analyst Osman Mirghani said the agreement is “merely a symbolic move” unless “developed further to a more concrete deal”, adding that “it will be hard to proceed with a comprehensive deal without agreeing with armed groups” amid its rejection by the SLM-MM led by Darfur governor Minni Minnawi and the JEM led by finance minister Jibril Ibrahim (AFP, 6 December). Bakri al-Jak also ruled out the implementation of the security arrangements stipulated in the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement. “This agreement is not enforceable for reasons related to financial capabilities for demobilisation and the lack of an integrated political vision of the security arrangements,” he told Radio Dabanga (4 January).

Therefore, Hafiz Mohammed, the director of Justice Africa Sudan, said the framework agreement “is not optimal” as “the problem with Sudan is not agreements, it is honouring those agreements”. He explained that Sudan has “civilian institutions which are not able to enforce and implement the constitutions and deals,” instead opting to “fold them on the junta” (Radio Dabanga, 5 December).

5. Solutions

Solutions provided for the implementation of the framework agreement have included policy suggestions for the pro-democracy movement inside Sudan (5.1), alongside western states who aim to support democratic development in Sudan (5.2).

5.1 Domestic solutions for the FFC-CC

5.1.1 FFC ceasefire with RCs

To win over resistance committees (RC), ICG (23 January) suggest the FFC can find common ground on the RC’s political charter and negotiate a “ceasefire” whereby RCs “stop campaigning against the accord, redirecting their energies toward holding signatories to account for what they have agreed to”.

5.1.2 FFC to make Khartoum-centric deal more inclusive

To make the “Khartoum-centric” deal more inclusive, ICG (23 January) call for engagement with local power brokers such as peripheral armed movement leaders and tribal chiefs. With the credibility of the civilian government hinging on the extent of its acceptability to a wide range of political actors, ICG (31 January) suggests that the FFC is encouraged to expand groups included in its ongoing negotiations with the military, and appeal to their interests by including their agenda items. ICG also warn that excluding Islamists not affiliated with ex-president Omar al-Bashir’s regime will “nurture ready-made and well-connected opposition that retains plenty of support among conservative Sudanese.”

5.1.3 Phase II negotiations focus on state-building

ICG (23 January) suggest that Phase II negotiations focus on core areas of state-building including: economic reforms, establishing an independent electoral commission, credible government administration, overseeing peace processes and pursuing a national constitutional dialogue.

5.1.4 Justice for Sudanese victims of atrocities

To help the Framework Agreement provide justice for victims of atrocities in Sudan, Rights for Peace (26 February), a charity that seeks to prevent genocide using human rights approaches, call for the:

Transitional Justice Coalition of over 30 Sudanese NGOs to enable the sensitive participation of conflict-related sexual violence survivors in regional workshops to ensure this category of victims is not excluded from the transitional justice discussions;

Political parties, mediators and other signatories to ensure participation of victims of human rights violations and their families, as well as pro-democracy activists, including women;

The Law Reform Commission and Constitutional Court to be established without delay to ensure reform of the justice sector and oversee the appointment of newly qualified judges to improve access to justice.

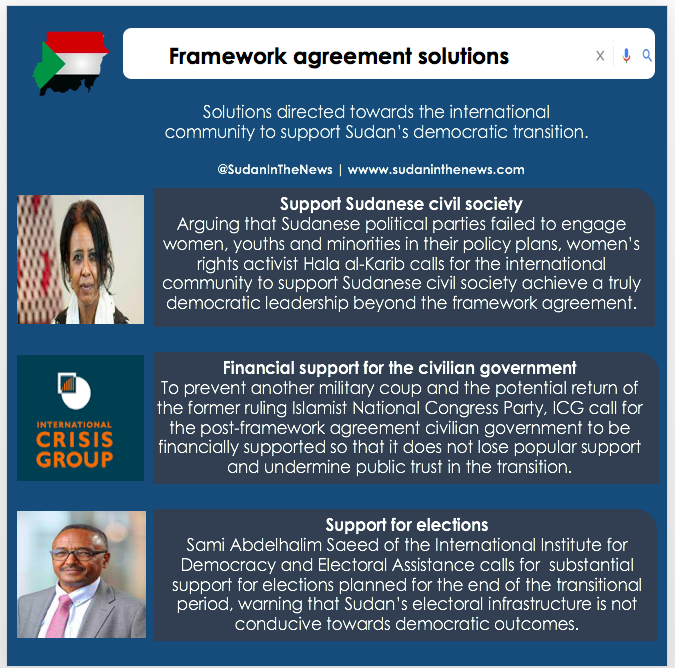

5.2 International solutions for Sudan’s pro-democracy movement

International support for Sudanese civil society

Hala Al-Karib, the Regional Director of SIHA (the Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa), calls for the international community to support Sudanese civil society achieve a truly democratic leadership beyond the Framework Agreement. Al-Karib argued that Sudan’s “weak and isolated” political parties’ attempts to lead the political transition after the revolution “were doomed to failure” as they had long lost any connection they had with the people, were solely interested in self-preservation and “failed to engage with and accommodate in their policy plans the new waves of activism led by women, youths and minorities” who were “truly responsible” for toppling Omar al-Bashir’s regime” (Sudan Tribune, 12 January).

International support for elections

Sami Abdelhalim Saeed of International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance calls for the international community to provide substantial support for elections in Sudan planned for the end of the transitional period. Saeed warns that the requirement in Sudan that elections happen at the end of a transition “places a huge burden” on Sudan’s unelected transitional institutions to develop a permanent constitution, to which the three “non-attractive” solutions are: amending the constitutional documents in contradiction of the Juba peace agreement, rush constitution-building and compromise on quality and inclusivity or delay elections and increase the risk of extra-constitutional military intervention (Atlantic Council, 30 January).

Financial support for civilian government

To prevent another military coup and the potential comeback of the former ruling Islamist National Congress Party, ICG (31 January) call for the EU to financially support the civilian government so that it does not lose popular support should it fail to adequately improve the livelihoods of ordinary citizens and undermine public trust in the political transition. ICG also propose that humanitarian relief focuses on health, food and education to provide stability.