DARFUR REPORT 3: February-March 2021 - Musa Hilal released, SLM-AW clashes, views on UNAMID and solutions

Summary

At the start of 2021, violence has continued to rise in Darfur, with more displaced (183,000) in three days of January alone than compared to the whole of 2020. In the West Darfur, the death toll of the January 2021 massacre in al-Geneina rose to 163, with the suspected perpetrators detonating a granite bomb in an attempt to escape detention. In South Darfur, recurring clashes between the Fallata and Masalit tribespeople killed 11, whereas in Jebel Marra, the holdout Sudan Liberation Movement faction of Abdelwahid al-Nur (SLM-AW) has claimed to kill government forces in ongoing clashes. The SLM-AW has also clashed with the government in North Darfur, which also witnessed the looting of a United Nations-African Union mission in Darfur (UNAMID) site and clashes between the Arabised Fur and Tama tribes that killed 11 – both in Saraf Omra.

In political news relating to Darfur, former Janjaweed militia leader Musa Hilal, accused of “serious crimes” in the Darfur conflict between 2002-2005 was released from prison, in what analysts state reflects a “new reality” in Sudanese politics whereby militant leaders from marginalised peripheries such as Darfur as seizing an opportunity for national leadership.

The key issues highlighted in this report are: the growth of inter-communal conflicts which are exacerbated by the grievances held by Arab tribes accused of being affiliated to the ousted al-Bashir regime. In addition, traditional conflict resolution methods are considered ineffective. Furthermore, government security forces are considered lacking the capacity to protect Darfuri civilians, as evidenced in their inability to collect weapons. Moreover, the war economy in Darfur provides financial incentives for rebel combatants, with the SLM-AW particularly profiting from gold-mines in its territories by buying weapons and recruiting fighters.

Several analysts, policymakers and activists continue to criticise UNAMID’s “premature” withdrawal, with the overwhelming theme being concerns about the capacity or willingness of Sudanese authorities in securing the region. Alongside calls for the UN to reconsider the end of UNAMID’s mandate, solutions for Darfur proposed by Sudanese civil society include: accountability mechanisms, transitional justice and for state authorities in Khartoum to deal with bringing violent perpetrators to justice.

Events

Musa Hilal free

Former Janjaweed militia leader Musa Hilal was released by Sudanese authorities following more than three years in detention (Radio Dabanga, 12 March). According to Human Rights Watch (15 March), Hilal “ gained notoriety playing a well-documented role leading the Janjaweed militia as serious crimes were committed in Sudan’s Darfur conflict between 2002 and 2005”. As noted by Reuters (15 March), human rights groups accuse Hilal of coordinating Arab militias blamed for atrocities in Darfur that left an estimated 300,000 dead and 2.5 million displaced, although Hilal claims that he mobilised his (Rizeigat) tribesmen to defend their lands after a government call to popular defence against non-Arab rebels.

Hilal attributed his release to meetings with Lt Gen Abdelrahim Hamdan Dagalo, Deputy Commander of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the brother of Himedti, RSF commander and deputy chairman of the ruling sovereign council, which pardoned Hilal after his arrest in 2017 for refusing to respond to the government’s disarmament campaign (Radio Dabanga, 15 March), although analysts suggest that Himedti’s rivalry with Hilal played a key role in the arrest of the latter.

Reuters (15 March) note that both Himedti and Hilal, who both hail from the Rizeigat tribe, “remain in competition for political and economic influence in Darfur”, with both holding gold mining interests and many Arab militias still active in Darfur remaining loyal to Hilal. Analyst Alex de Waal wrote that Himedti’s rivalry with “his former master [in the Janjaweed militias]” Hilal intensified after gold was discovered in North Darfur’s Jebel Amir in 2012 (BBC, 20 July 2019). Indeed, researcher Jerome Tubiana suggested that Himedti “eventually managed to have his rival [Hilal] arrested in 2017” after competition for gold concessions (Foreign Policy, 15 May 2019).

Crucially, the apparent reconciliation between Darfuri rivals Hilal and Himedti may have a major impact on Sudan’s history and political make-up. Yousif al-Sondy argues that Hilal’s release with Himedti’s assistance, and Hilal’s recent meetings with rebel leaders Minni Minnawi and Yasser Arman, reflects a “new reality” in which leaders from Sudan’s marginalised peripheries have their “greatest chance for leadership”. Al-Sondy argues that years of wars triggered by the center’s underdevelopment of the peripheries means that the former is no longer in a better condition than the latter, leaving Sudan in a delicate “balance” that can culminate in either: a) the beginning of a unified new Sudan or b) “the fragmentation of Sudan into many states” (al-Rakoba, 14 March).

West Darfur

Radio Dabanga (26 January) reported that the death toll of the massacre in al-Geneina, West Darfur rose to 163, with the local Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) committee attributing the incident to “a political struggle supported by elements of the former regime who have taken advantage of tribal divisions”. Meanwhile, Arab tribespeople in al-Geneina held a sit-in against the local government – demanding the removal of camps for internally displaced persons. However, al-Geneina’s Resistance Committees claimed: "the sit-in was started in the name of certain tribes and was led by a number of supporters of the ousted Omar al-Bashir regime" (Radio Dabanga, 29 January).

Imprisoned suspected perpetrators of the Kerending displacement camp massacre then allegedly attempted to escape prison through the explosion of a bomb. Kamal al-Zein of the High Committee for the Management of the West Darfur Crisis, who made the aforementioned claims, also accused Public Prosecutor of complicity for not lifting the immunities of those accused of participating in the massacre, “most of whom are Rapid Support Forces personnel” (Radio Dabanga, 5 March).

South Darfur

In Gireida, South Darfur, 11 killed and 26 wounded in recurring tribal clashes between the Fallata and Masalit tribes stemming from cows being stolen (Radio Dabanga, 4 March). In Jebel Marra, South Darfur, 3,000 were forced to flee after gunmen attacked villages on consecutive days – leading to 11 being killed, dozens wounded and others missing (Radio Dabanga, 27 January).

In eastern Jebel Marra, the holdout rebel Sudan Liberation Movement led by Abdel Wahid al-Nur (SLM-AW) – which maintains its stance of refusing to enter peace talks - accused a "government militia" of launching a three attacks in ten days on their positions. Following an alleged attack on 25 January, SLM-AW military spokesman Walid Mohamed Abaker “Tongo” claimed that his group killed 17 gunmen and wounded a further 23 the following week (Sudan Tribune, 1 February). Four days later, Tongo claimed that the SLM-AW killed 24 gunmen, captured a soldier and seized weapons (Sudan Tribune, 5 February).

North Darfur

The SLM-AW have also been active in North Darfur, where the Tongo claimed that they repelled an attack in Touha Shalal, Tawila locality (Radio Dabanga, 1 February). In Saraf Omra in North Darfur, a site of the United Nations-African Union mission in Darfur (UNAMID) was ransacked and ‘levelled’ by looters on February 17, just weeks after it was handed over to the Sudanese government (Radio Dabanga, 24 February). Also in Saraf Omra, at least 10 were killed 32 were injured in tribal clashes, with the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC)* saying that 16 families and a total of 74 individuals had been displaced after their homes were burned during the clashes (Radio Dabanga, 9 March).

Reports provide conflicting accounts of the origin of the dispute between the Tama tribe and the Arabised Fur tribe. Radio Dabanga (4 March) sources said clashes erupted following preparations for the reception of Sultan Mohamed al-Tama, with several groups, including a Fur group, denouncing the organisation of an event celebrating his reception. However, AP (3 March) report that the dispute originated over a piece of land. Nonetheless, the security committee in charge of dealing with the escalated security situation in Saraf Omra arrested 10 leaders from Fur and Tama tribes (Radio Dabanga, 9 March).

7 key issues

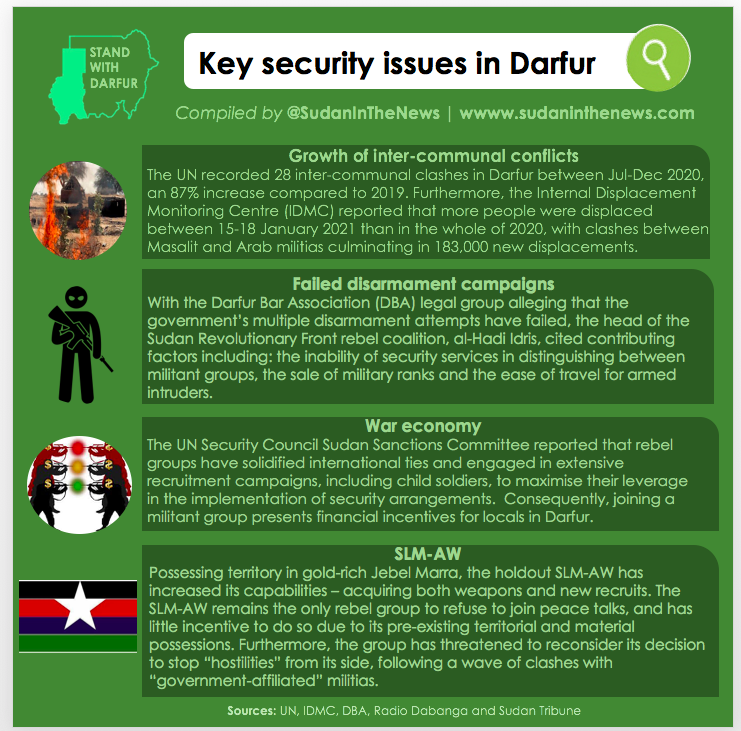

The growth of inter-communal conflicts

AP (February 10) attribute the fighting in South and West Darfur which killed around 470 to “a familiar scenario: a dispute between two people or a minor crime turning into all-out ethnic clashes.” Indeed, the same article reference a UN experts report covering March to December 2019 which said tribal clashes and attacks on civilians increased sharply “in both frequency and scale,” with acts of sexual and gender-based violence committed daily and going unaddressed.

Furthermore, Amnesty International (1 March) note that the UN “recorded an alarming increase in inter-communal clashes in Darfur, with 28 incidents between July and December 2020, an 87% increase compared to 2019”. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC, 18 February) the “unaddressed” conflict triggers: ethnic disputes between herders and farmers over scarce resources overlap with disasters such as flooding and political instability.

IDMC further note that in January, more people were forced to flee their homes in three days between 15-18 January, than in the whole of 2020, with violence between armed militias from the Massalit and Arab communities culminating in around 183,000 new displacements, alongside displacements in West Darfur’s al-Geneina, South Darfur’s Gereida and Jebel Marra and North Darfur’s Tawila.

2. Arab grievances

As the revolution attempts to address inequality between non-Arabs and Arabs in Darfur, Arab communities are revealing grievances over land, power and resources. In West Darfur, Arab tribespeople held a sit-in demanding the dismissal of the local governor, who belongs to the Masalit, a non-Arab sedentary tribe, alongside his employees. As previously mentioned, the local resistance committee distanced themselves from a protest it said was organised by those affiliated with the former ruling regime of Omar al-Bashir. In addition, the Arab tribespeople demanded the removal of camps of internally displaced persons (Radio Dabanga, 29 January), which emphasises ethnic competition over land in Darfur.

As noted by Sudan Tribune (2 March), land ownership is a key demand of Darfur war victims, but there are fears that the expulsion of [Arab] settlers in areas deserted by the displaced and refugees will lead to the outbreak of new conflicts in Darfur. The matter is further complicated by the usage of traditional conflict resolution methods for land disputes.

3. The use of traditional conflict resolution methods

Sudan Revolutionary Front rebel leader and member of the ruling sovereign council Hadi Idris, said that the soon-to-be established Land and Hawakeer Commission will use traditional conflict resolution methods and customs to ensure the return of the displaced to their areas and to resolve the conditions of settlers (Sudan Tribune, 2 March). However, as reported by Radio Dabanga (2 March), South Darfur governor has reiterated his rejection of any inter-ethnic conflict resolutions through traditional reconciliation conferences, with the article noting that reconciliation conferences between Fallata herders and Masalit farmers failed to bring peace to Darfur. With conflict resolution continuing to pose an obstacle to security in Darfur, concerns remain that Sudanese authorities are unable to contain the violence.

4. Limited government capacity

Mohammed Osman, a researcher at HRW, noted that witnesses to the deadly fighting in South and West Darfur said that the response of the government forces was “too little, too late” (AP, 10 February). In the case of the clashes in Gireda, South Darfur, which killed at least 11, locals reportedly alleged that two attacks in consecutive days “took place before the eyes of the joint forces” (Radio Dabanga, 3 March). In North and South Darfur, protests have erupted over the alleged inaction of security forces, with demonstrators demanding the resignation of local governors, Mohammed Arabi and Mousa Mahdi respectively (Radio Dabanga, 11 March). In Arabi’s case, the local Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC) committee claim that he did not intervene despite prior warnings about the “tense situation”. Furthermore, the government is accused of failing to disarm militias accused of the violence in Darfur.

5. The inability to collect weapons

A key obstacle to security in Darfur has been the failed disarmament process. Radio Dabanga (10 February) report that the Darfur Bar Association (DBA) legal group alleges that the government fails to collect weapons in Darfur despite multiple attempts. Noting the proliferation of militiamen in several major towns and cities, especially in Nyala, Zalingei, and Kabkabiya, al-Hadi Idris cited the inability of “leaders of the security services [in distinguishing] between the signed and non-signatory movements [of the peace agreement]” as a contributing factor. He also warned of “the massive proliferation of armed intruders who travel regularly and carry out assassinations and violations”, and referred to “the widespread sale of military ranks from the rank of major general and below”, describing them as “fraudsters” (Radio Dabanga, 10 March). Indeed, the proliferation of weapons and militias in Darfur contribute to a war economy that provides financial incentives for militias and rebel combatants.

6. The war economy

Nafisa Hajar, head of human rights at DBA, said that children are being forcibly recruited by armed groups (Radio Dabanga, 10 February). As reported by the UN Security Council Sudan Sanctions Committee, Sudanese rebel groups engaged in extensive recruitment campaigns and recruited child soldiers to maximise their leverage in the implementation of security arrangements (Sudan Tribune, 26 February). It is also claimed that the rebel groups have international ties, with Sudan Tribune adding that they “consolidated their relations with Libyan parties and their backers particularly: the UAE, who convinced them to leave some troops in Libya.”

With rebel groups competing over resources and territory, it also claimed that inter-fighting between different rebel groups reportedly displacing over 20,000 civilians, with the rebels reportedly committing human rights violations. Consequently, the UN has threatened to sanction all Darfur armed groups, whether signatory or non-signatory to the Juba peace agreement. One of the rebel groups that is particularly accused of funding militancy in Darfur is the SLM-AW, who remain the only rebel group to refuse to enter peace talks.

7. The SLM-AW in Jebel Marra

The SLM-AW has reportedly increased its capability by recruiting new fighters and purchasing weapons, thanks to its territory in Jebel Marra, a site rich with gold mines (Sudan Tribune, 26 February). As the only rebel group that refuses to hold peace talks, the SLM-AW both rejected the Juba Peace Agreement and accused the armed groups who signed it of “seeking government jobs” (Sudan Tribune, 1 February).

Given that the SLM-AW’s territory and access to gold mines provides it with no financial incentive to end the rebellion, it has strong bargaining power with regards to conflict and it can defer being co-opted by the government. Indeed, SLM-AW spokesperson Tongo stressed that “the repeated attacks” may push the SLM-AW to reconsider its decision to stop “hostilities” from its side, which it claims it has been abiding by “despite repeated acts of aggression against SLM-AW in areas it controls” (Radio Dabanga, 1 February).

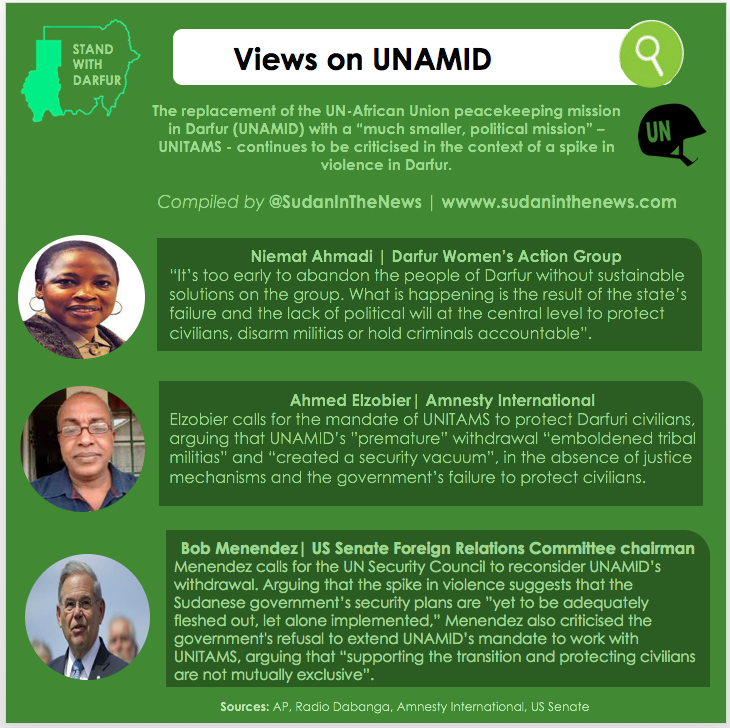

4. Views on UNAMID’s “premature” withdrawal

AP’s (10 February) feature piece states that the “latest burst of violence” after the joint U.N.-African Union peacekeeping force that had been in Darfur (UNAMID) for a decade ended its mandate, and was “replaced with a much smaller, political mission [UNITAMS]”. Indeed, the end of UNAMID’s mandate continues to be criticised in the context of rising violence in Darfur, with several activists, analysts and analysts expressing concerns over UNAMID’s “premature withdrawal”.

John Prendergast (The Sentry)

John Prendergast, co-founder of The Sentry, an organisation that tracks human rights violations in Africa, was quoted by AP (February 10) to say: “anyone could have predicted that as soon as the UN troops departed, some of these militias would begin attacking”.

US Senator Bob Menendez

US Senator Bob Menendez, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (25 February), calls for US President Joe Biden to appeal to the UN Security Council to reconsider UNAMID’s withdrawal. The rising violence in Darfur suggests that the Sudanese government’s security plans "have yet to be adequately fleshed out, let alone implemented", argues Menendez. “Most worryingly”, Menendez adds, those likely to be charged with protecting civilians in Darfur, including components of the Sudanese military and the RSF “are the same actors that for years worked to implement Omar al-Bashir’s campaign of terror and genocide.”Menendez further criticised the government’s refusal to extend UNAMID’s mandate to work with the “political” UNITAMS, stating that “supporting the transition and protecting vulnerable civilians are not mutually exclusive”.

Ahmed Elzobier (Amnesty International)

Echoing Menendez’s calls for the UN Security Council to “re-evaluate the security situation in Darfur”, Ahmed Elzobier, Amnesty International (1 March) researcher for East Africa, also calls for the mandate and resource of UNITAMS to “protect civilians in Darfur until Sudanese military and civilian leaders prove they are willing and able to protect them.” Elzobier argues that “premature withdrawal of UNAMID” alongside the “the failure of Sudan’s government to protect civilians [and] the weakness or in some cases, lack of, justice mechanisms” have emboldened some tribal militia fighters in Darfur to indulge in gruesome acts of violence”. Elzobier concludes UNAMID’s “premature withdrawal has created a security vacuum in Darfur and exposed civilians to violence”.

Niemat Ahmadi (Darfur Women Action Group)

Similar criticisms of the Sudanese government’s capacity to secure Darfur came from Niemat Ahmadi of the Darfur Women Action Group, who said: “it’s too early to abandon the people of Darfur without sustainable solutions on the ground. [Al-Geneina massacre] is the result of the state's failure and the lack of political will at the central level to protect the civilians, disarm militias or hold criminals accountable” (Radio Dabanga, 25 January).

Solutions

Accountability mechanisms

Alongside calls for Sudanese authorities to “vigorously investigate” Musa Hilal, Human Rights Watch (15 March) assistant researcher Mohammed Osman suggests that the government “should also take concrete steps towards establishing and operationalizing accountability mechanisms laid out in the Darfur peace agreement that include cooperation with the International Criminal Court and setting up a special court for Darfur”.

Transitional justice

Protesters in Gireida, South Darfur, demand that state authorities prosecute criminals, form an international investigation committee into the recent violence, compensate those affected by recent arson attacks, recover looted property, enforce the rule of law, and provide shelter material for the newly displaced. The protesters stressed that displaced people must be enabled to return to their villages and engage in agricultural, pastoral and commercial activities (Radio Dabanga, 10 March).

State authorities in Khartoum to deal with cases

Kamal al-Zein of the High Committee for the Management of the West Darfur Crisis accused the Public Prosecutor of complicity for the massacre in al-Geneina and the subsequent prison escape attempt of arrested suspects, alleging that the prosecutor did not lift the immunities of those accused of participating in the massacre, “most of whom are RSF personnel.” Thus, al-Zein demanded that cases are transferred to Khartoum, warning that the absence of accountability would lead to repeated massacres. He also spoke of “deteriorating humanitarian conditions in 25,000 shelters for the displaced,” calling for food and medical aid supplies and the immediate initiation of transitional justice in West Darfur (Radio Dabanga, 5 March).